What is machinery installation?

Machinery installation is an essential phase in every machinery’s lifecycle. It’s the first moment of bringing machinery into production.

Why is proper installation necessary?

The installation process has a direct impact on the machinery. It’ll determine the operating conditions in the performance and lifecycle cost. How the machine gets installed determines how it’ll behave. Thus, it helps to minimize premature failures once installed.

Elements of a proper machinery installation program:

Proper installation can be broken down into three main elements. These are:

- Integrity

- Strategy

- Planning

Our focus for this session falls on integrity.

What is Integrity?

Integrity is showing consistent adherence to moral or ethical procedures. It’s when you stick to what you say you’re doing. There’s usually a lot of stress, deadlines, and a lot of equipment to install at the site. You have different cultures coming together. That’s because everyone is used to working in a certain way.

Integrity thus helps to create trust in the procedures you wish to undertake. It also ensures the people you’re working with are taking their roles seriously. Integrity applies to all involved individuals, from the installers to the project manager.

How do you leverage integrity?

Integrity must be addressed from the onset of the project. Afterward, you need to give your team the time and space to handle their specific duties. The API Recommended Practice 686 offers recommended practices for machine installation. That means you only need to collect the necessary data as you’re not inventing anything.

There are a lot of standards to follow to have the correct procedures. These include ANSI standards, ISO standards, and API standards to outline proper procedures.

But you may come across machines or a layout that wasn’t designed properly. Such an issue makes it difficult to install it correctly. For this, you need to inform everyone involved so that you can raise their awareness levels. Those involved in the installation with then be able to tell you the way forward. This helps to mitigate whichever risks could come about.

Hear more from Roman Megala with Easy-Laser in this podcast by James Kovacevic and learn more on how to improve your machinery installation process!

Download our 5 Element Machine Installation Infographic to help you outline 5 important elements of machine installation including Foundation, Anchoring, Isolation, Baseplate Level, and Flat plus Alignment. Together with our Easy-laser XT770G shaft alignment system plus the addition of our versatile XT20 laser transmitter, measure the straightness and flatness of machine foundations and bases with precision and reliability!

Related Blog: Top 10 Machinery Installation Issues

by Diana Pereda

We previously discussed in this series, Environmental Compliance Through Efficient Work Practices: Part 1. In this blog, we discuss goals for efficient work practices like proper alignment and belt alignment.

Upgrading tools and introducing more complete training should be part of any company’s operating plan, so we will see how much impact can be made by implementing solid information and work techniques that can impact the output of the machines, the reduction of stress of maintenance, and the achieved realization of environmental compliance.

Proper alignment

In cases where an engine is running outside parameters for alignment, there is additional power consumption from the deformation of the coupling, the crankshafts, and the bearings. Having an alignment even a few thousandths of an inch outside of specifications can create enough bind to require 50-100 horsepower on a large engine. While that is not a lot for an engine rating 1780HP, it is enough to possibly put it over the permitted level, and incur a fine (in some states, that fine can be as much as $30,000 per day, back to the last time it was proven to be passing). Providing an accurate alignment procedure and using proper tools, we can expect to reduce that parasitic loss right at the point of power transmission and give that engine a cushion should the load be increased later for actual production demands.

Belt alignment

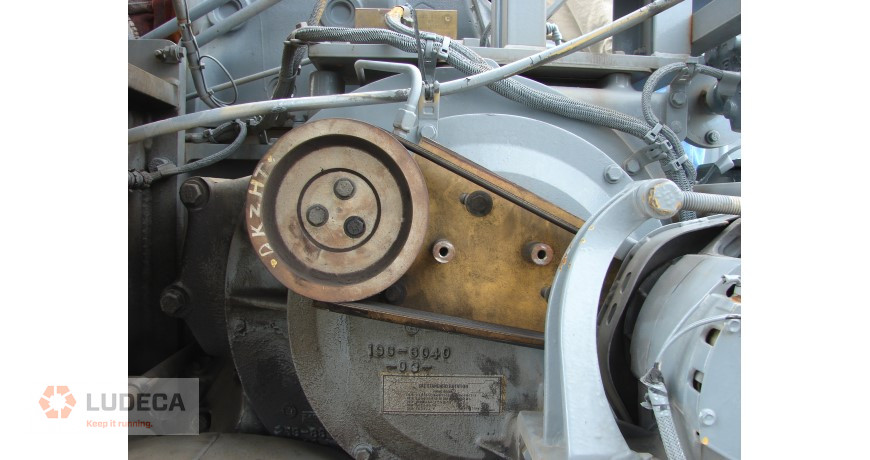

A large number of these engines have huge cooling systems that are driven by the auxiliary drive of the engine. The belts that transmit this power can be massive, and leave the pulleys huge. Misalignment of these pulleys makes the belts deform and consumes power by constantly flexing. This also generates high working loads at the bearing that supports those pulleys. As the lubricant works harder within that bearing, it breaks down, and the bearing becomes harder to rotate. Again, we have a situation where the engine is being tasked extra to make up for these losses. Having an accurate system such as the Easy-Laser XT190 for proper pulley alignment can greatly reduce the power this sub-system requires for basic operation.

Stay tuned for my final blog of this series where I discuss proper adjustment of cooling fan blades and the right amount of lubricant needed for bearings!

Related blog: Guidelines for Proper Belt Installation including Sheave Pulley Alignment

by Diana Pereda

Midlands Technical College students are learning on the cutting edge of industrial training thanks to a dedicated instructor and a leading maintenance solutions provider.

Matthew Lester is a member of the Industrial Maintenance faculty in the School of Advanced Manufacturing and Skilled Trades at MTC in Columbia, S.C. In 2019, he worked with LUDECA to install a donated laser alignment system at the college. Since then, Lester secured funding that allowed for instrument upgrades to the donated system.

Now, new Easy-Laser XT series laser alignment systems and accessories are up and running. “Students, instructors, and experienced employees like the touch screen option and having access to the manual on the control unit,” said Lester. “Plus, the responsiveness and accuracy of the XT440 are unmatched.”

Thanks to tenacity and generosity, students at Midlands Technical College can work on five XT series laser shaft alignment tools and an XT190 belt alignment tool. MTC is at the forefront of maintenance reliability training programs in South Carolina.

To learn more about MTC shaft alignment courses, please click here. You can also contact Mr. Matthew Lester at: le*****@**********ch.edu.

Thank you Matthew for sharing your success story with us!

by Diana Pereda

While it is now the norm to see technicians using laser tools to perform shaft alignment on rotating machinery at a plant or facility, it was not too long ago that sheaves and sprockets were still aligned with a string or straightedge. Although it is still common to see technicians break out the straightedge when aligning sheaves or sprockets, lasers for belt alignment are finally starting to be utilized more at facilities—even though that system may be a visual-type laser and target system. Download our 5-Step Sprocket Alignment Procedure – a simple and effective procedure for sprocket alignment of chain-driven equipment.

Those systems are easy to use and have the benefit of a steady and weightless laser line reference to help get your sheaves aligned versus the old straightedge or string technique.

As good as those systems are, however, there is still more to be desired…

A modern belt alignment system utilizes a position sensing detector or PSD that allows for repeatable measurements and real-time adjustments to be made. Additionally, the software that these systems can run on is easy to interpret and has the advantage of being able to generate reports. Which, in this reliability-centered world is a big plus.

Here are some advantages of modern laser belt alignment systems over the older visual systems:

- More accurate

- Simplicity in measurement and interpretation

- Repeatable

- Can produce reports

- Can justify their cost in energy savings alone

So, save time and money by using or upgrading to a modern laser belt alignment system!

Related Blog: The Importance of Belt Alignment

by Diana Pereda

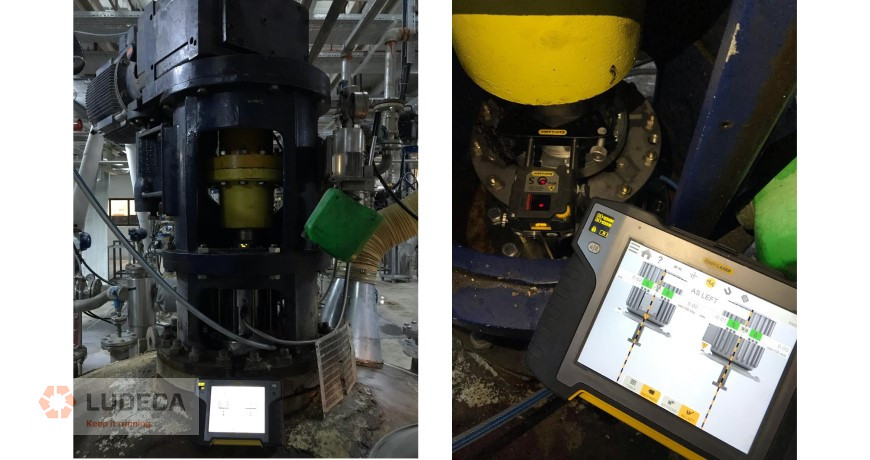

In vertically oriented shaft alignment, the objective is to make sure that the rotating axes of both shafts are lined up at the coupling during operating conditions. There are sometimes extra constraints such as plumb, which need to be taken into consideration. In this application, we have a typical vertical water condenser pump in which the pump housing has already been grouted into place.

The alignment of the motor shaft to the pump housing shaft needed to be inspected, and if necessary, corrected. The Easy-laser XT laser alignment system was chosen for this task. The compact wireless sensor units were installed on both shafts. Wireless is an advantage in this application as there are no cables to get tangled as the shafts are rotated. Once the sets of readings were taken, corrections were made by translating the motor to correct coupling offset and shimming on the motor flange to adjust the shaft angle. These corrections were calculated by the built in vertical alignment program of the XT laser alignment system. The corrections were monitored live with the system.

The results were documented and sent wirelessly via email to the customer. The result was that the alignment defects of the asset were identified, removed and documented in a short time.

Related Blog: How to Determine a Vertical Pump’s Natural Frequency

by Diana Pereda

This is a comment we hear all the time when someone buys a new laser alignment system. The assumption is that the cost of the system should magically make any alignment perfect, with little to no additional input from the technician. Nothing could be further from the case. In reality, the laser shows how inaccurate many work practices have become, as we depend more on technology. There are many factors that determine how an alignment job goes, and it’s time we discuss them. Without addressing these issues, the laser system will only continue to give us indications of how wrong things are.

- Mounting surface: Most equipment manufacturers give a specification of what type of surface material and surface finish should be present for the mounting of the equipment they sell. Whether that is a fabricated steel base, a concrete pad, or even a grout box, the expectation is that it meets the installation guide for how well the footprint of the machine mates to that surface. The idea is to get the maximum contact patch of a clean foot to that clean base. Any irregularities, voids, or contamination can allow for unintended movement. And that movement could be happening while trying to perform an alignment, or even worse when the machine is running.

- Mounting evenness or flatness: Knowing that the surface is ready to receive a piece of equipment goes a long way towards a smooth installation. Often, shims from equipment previously in place are reused to mount a new component. The thought is that it worked for the last one, so it should be fine for this new one. Most of the time, this is simply incorrect. Most quality rebuild shops machine the feet of a motor or pump as part of the overhaul process, to make them all coplanar, or even. It makes sense to make sure the base is even as well. If you establish that the base is flat, or at least shimmed flat before the new equipment is put in place, the installation goes much faster, and the alignment is easy to perform. Soft Foot should be practically eliminated by doing this step. (More on that in a bit.)

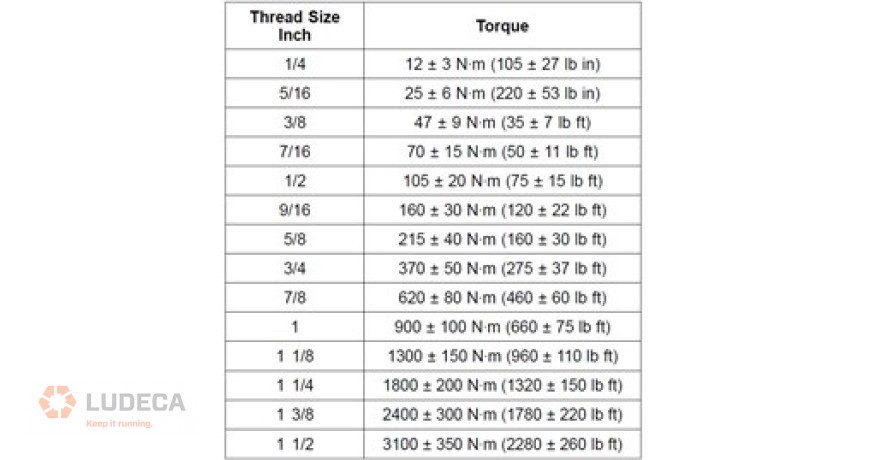

- Proper hardware and proper torque: OEMs are great at publishing specifications and possibly even giving recommendations for how to meet those specifications. What they count on is that everyone is aware of those requirements and how to achieve them. This means that when a torque spec is given, everyone from the design to the installation team should understand what size and grade of the fastener are required to meet that spec. Torque specifications for general fasteners are the same, no matter what industry. This means that if the bolt is 7/8″ in thread diameter, the general torque is 620Nm (or 460 lb/ft in old school terms), regardless of the setting. The only time these specs change is when it is in a specialized application, and at that point, specific torque charts are supplied. The main goal is to be consistent with the torque of hardware, so variables are not introduced from human inputs.

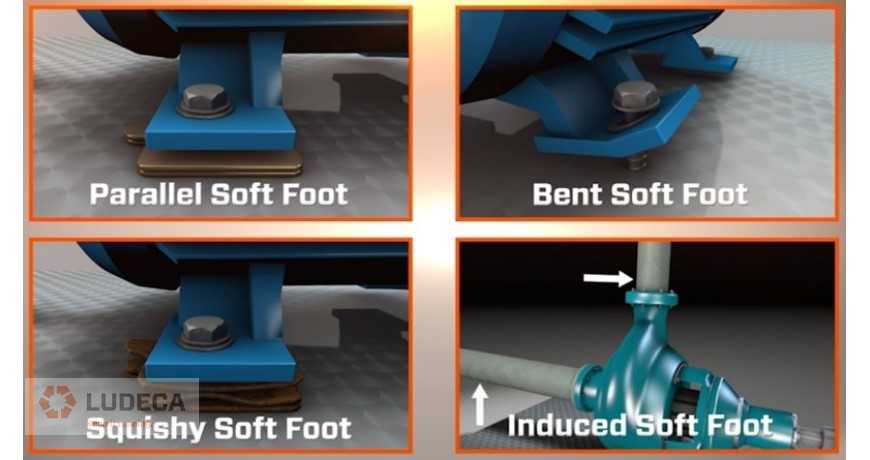

- Soft Foot: Ludeca has spent a large amount of time and resources trying to make the world more aware of soft foot conditions. We have videos, white papers, infographics, webinars, and in-depth diagnostics charts on the topic. The main takeaway is that if soft foot (i.e., machine frame distortion) is not eliminated, there is always an opportunity for unintended movement of the machine. It is simply not mounted correctly in some way even (including external pipe strain), and that situation is making it hard for the alignment to be done accurately, and hold the proper position when in service. When watching the outputs from a quality laser alignment system, if the tech sees numbers changing while tightening anchor bolts, that is an indication that soft foot is present. Visit our Knowledge Center for resources and tools to help you succeed when implementing and using our maintenance technologies.

- Second-guessing: The laser system is telling the tech one thing, but the thought is that the system is wrong. But something is occurring for the laser to give that information. Moreover, all of that information was gathered using inputs from the tech. The laser system is basically a computer with sophisticated optics attached, which means that “bad information in equals bad information out.” A better understanding of how the system calculates results makes it much easier to understand why those results are displayed. Training is the best way to resolve the confusion. Some companies buy laser systems, thinking that it will resolve all issues from alignment work and make the plant more reliable. In fact, this sometimes goes the other way. If the staff has been doing things a certain way for enough time that it becomes standard operating practice, the introduction of the laser might highlight how those practices were actually contributing to failures. Proper training not only shows the tech how to turn the system on but also shows how to achieve the best results for alignment. Sometimes, that training can identify issues that have been plaguing an operation for years, and actually, make life easier by not “fighting with the tool.”

Related Blog: What makes a laser shaft alignment tool accurate?

by Diana Pereda

Soft Foot has often been noted as the most inexact science part of the shaft alignment job. Historically, when people think of Soft Foot, they often want to neglect, ignore, or otherwise do everything possible to not deal with it. This is one of the traps that leads down the path of bad habits, bad alignments, and more problems down the line.

Shaft alignment can be thought of as two things:

- Aligning the shaft centerlines of rotation

- Checking for and correcting Soft Foot

Soft Foot, in fact, plays so much of a role in shaft alignment, that if one were to analyze the 5-Step Alignment Procedure below, one can see that Soft Foot appears in 2 out of the 5 steps. Therefore, Soft Foot can be thought of as almost half the alignment job.

5-step Alignment Procedure:

- Pre-alignment checks – including inspection and cleaning of machine supports

- Rough alignment – “eyeball clean” (with bolts loose) and Rough soft foot Loosen all bolts and “fill any obvious gaps”.

- Initial alignment – Get to within 5 to 15 mils at coupling or less than 20 mils at feet.

- Final soft foot – All feet less than 2.0

- Final alignment to tolerances and documentation

What is Soft Foot? Soft Foot is Machine Frame Distortion.

How does it happen? Soft Foot can happen from several things, including:

- Bent Feet

- Bad Bases (warped, uneven, flimsy)

- Dirt, rust, corrosion under feet

- Excessive or missing shims under the feet

- Pipe stress

- And any combination of the above…

What should be done about it?

A full and extensive diagnosis should be done on every machine foot to determine whether or not the tightening of that particular bolt is causing machine frame distortion, and thereby causing shaft misalignment or machine frame strain.

A few helpful tips to remember are:

- Minimize total number of shims under each machine foot to no more than 4 shims per foot.

- Make sure the area is clean, including machine feet, bases, shim packs, etc.

- Jack bolts should be backed off, so they don’t interfere with the soft foot check.

- When checking for soft foot, only one machine foot should be loosened at a time, and the deflection or movement at the shaft noted.

In conclusion, soft foot plays a big role in machine reliability and therefore should not be ignored. Laser alignment systems such as the Easy Laser XT series can help diagnose and correct soft foot.

Read: Common Causes of Machine Failure: #2 Soft Foot

by Diana Pereda

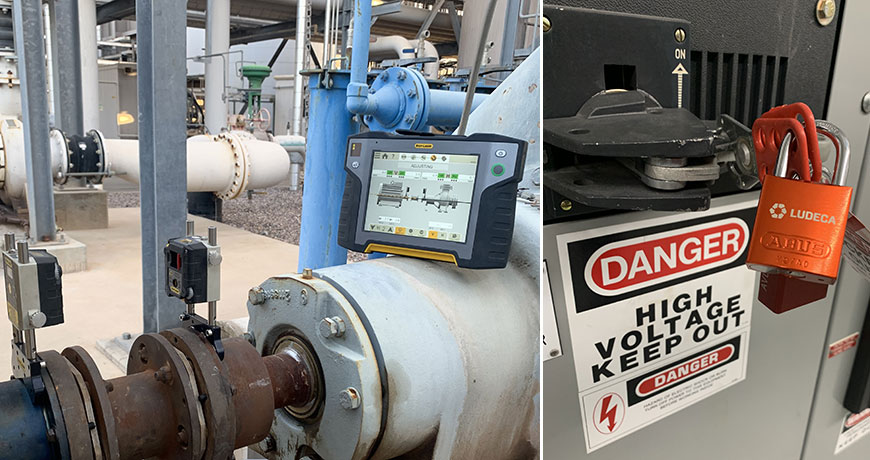

Before going on a trip, we typically plan ahead. What we are going to do, what we are going to pack, where we are going to go, and places to visit each day of the trip. When starting an alignment job, it is not that different. We must plan ahead. This means being ready to thoroughly clean the mounting base, having the right tools for the job at hand, and allocating the necessary number of hours to get the job done right.

Proper preparation for success can go a long way. Cleaning underneath the feet of the machinery will greatly decrease the chances of having a soft foot, thereby increasing the machine’s ability to respond accurately to corrections. Also, check under the entire machine for loose debris. Foreign objects under the machine can cause soft foot as the machine is lowered during alignment corrections even though the feet of the machine and shim packs are spotless. Another thing that should be considered during pre-alignment is having the right set of shims. These must be the right size for your application, corrosion-proof, and made from high-strength material. They should also be free of burrs, bumps, nicks, and dents of any kind. But first and foremost is planning for safety. Locking out/tagging out the machines is the VERY first step before starting the alignment process. Getting the right training to operate your laser alignment system and understanding misalignment will also save time and ensure success.

Let’s summarize a few of these important planning and execution steps:

- Lock-out and tag-out

- Thoroughly clean the mounting base and feet

- Visually inspect for foundation, grout, and baseplate defects, and wear and tear

- Make sure to have the right tools for the job

- Make sure to have the right shims

- Inspect and replace damaged shims

- Allocate the right amount of hours

- Have the right training

- Make sure your high-quality laser alignment system, such as an Easy-Laser XT770, is charged and all components and needed accessories like specialty brackets are there.

Download our 5-Step Shaft Alignment Procedure for a simple and effective procedure for shaft alignment of rotating equipment!

Related Blog: Pre-Alignment Checks plus Essential Clean-up and Preparation Tasks

by Diana Pereda

March 2021 – Pumps & systems

In olden times, when hard work beyond the ability of a few humans was needed, a horse or a team of oxen was the solution. Even greater power requirements were fulfilled by wind or watermills. This form of driving machinery lasted for centuries and the mechanical components involved required little in the way of alignment, beyond rudimentary good fits. When self-powered machinery was invented in the early 19th century in the form of James Watt’s steam engine, the pace of industrialization began to quicken. With this revolutionary power source, the volume of manufacturing increased rapidly and a greater demand for water and other fluids in industrial processes was created.

While early machinery often transmitted power via gear drives and flat leather belt drives, it did not take long for engineers to realize that directly coupling the driver to the driven machine would result in improved efficiency of power transmission with all the savings entailed therein. It is only with the invention of modern multiple V-belt drives with negligible stretching and slippage that the efficiency of belt-driven systems again rose to compete effectively with direct-drive systems.

In early days, speeds of rotation were slow and alignment of both belt-driven and directly coupled machines was traditionally accomplished by eyeing it, using a straightedge and feeler gauges. Good machining of surfaces and great care was usually all that was needed to obtain a satisfactory result. This modus operandi persisted through the 1940s. By the end of World War II, the United States was in a commercial position that favored industrial production: almost all of the world wanted manufactured goods, and the U.S. was a principal source for them. If someone wanted a car, a TV, or a sheet of stainless steel, it was likely made in the U.S. Global competition did not exist to nearly the extent that it does today, so cost-consciousness was not what it is today. Resources were plentiful, environmental regulation minimal, and craftsmanship excellent. Plants could afford to install standby machines for all critical processes and concrete foundations were poured a little deeper. People designed machines using slide rules. Today, computers trained to shave away every unnecessary ounce of metal do the designing.

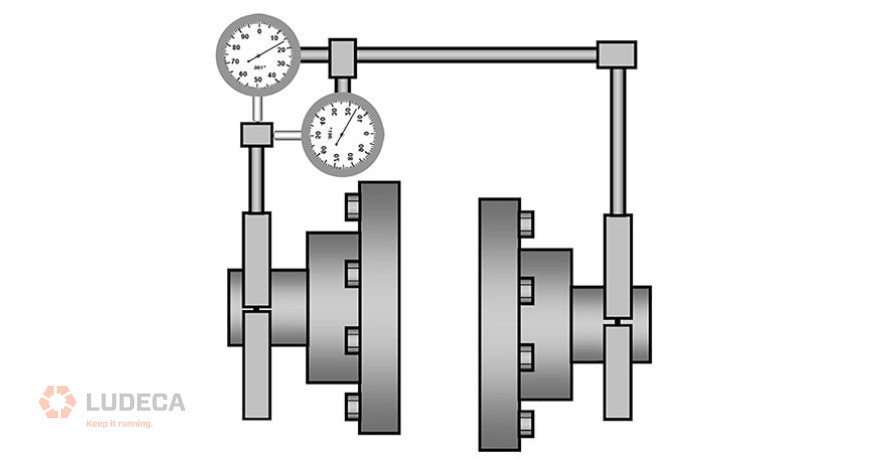

In the 1930s, the average speed of rotation of an electric motor was 900 or 1,200 rotations per minute (rpm). Back then, the straightedge was king. Pumps had stuffing boxes, and when they sprang a leak, the mechanic simply tightened the packing glands to compress the braided cotton and asbestos packing rope until the leak went away. Often, the shaft was later found to be scored from the pressure of overtightening. As industrial production flourished and a wide range of new products were introduced, harsh chemicals demanded different containment approaches and mechanical seals became more prevalent. This demanded precision alignment. As technology improved, and Europe came online again with significant industrial production, the 1950s saw speeds of rotation increase to an average of 1,800 rpm. It was quickly discovered that as speeds of rotation increased, the need for good alignment also increased—not just in linear proportion, but exponentially.

The straightedge could do a fine job with offset misalignment if used with care on coupling surfaces of well-bored couplings; but who could consistently guarantee such conditions? Yet, it was not good enough with regard to the angularity between the shafts. This was due to the limited measurement resolution afforded by eyesight over the short span of the straightedge across the coupling hubs. As apprenticeships and general craftsmanship declined, the assurance that coupling was machined concentric to the mechanical centerline of rotation, and that its faces were perpendicular to said centerline, or even that it was entirely round, waned. Also, foundations became weaker and not as flat as they ought to have been. Put simply, the alignment of surfaces via a straightedge or a dial indicator rotated around a shaft (not with the shaft) was no longer good enough. New ways to align the actual rotating centerlines of machines needed to be devised, and now the dial indicator (formerly strictly a machinist’s tool) came into its own. Its use by millwrights in machinery shaft alignment did not really take off until after WWII. Now the so-called “rim and face” method became king.

Click here to continue reading the entire article: Reduce Errors From Poorly Designed Machinery by Alan Luedeking

by Diana Pereda

When you are bolt-bound or base-bound on a critical machine train—usually one that is very difficult to move—it is not enough to just fix (make stationary) individual pairs of feet to obtain alternative shimming or moving solutions. You need even more flexibility, such as the ability to minimize moves across all the feet. The concept of stationary and movable machines is obsolete: all machine feet are movable under given circumstances, so it is essential to be able to find the minimum corrections necessary to align to any conceivable centerline, including fully optimized centerlines or centerlines optimized for any desired number and combination of fixed and movable feet. Such flexibility is imperative when working with machinery on the critical path. Therefore, look for this capability when selecting your next laser shaft alignment system.

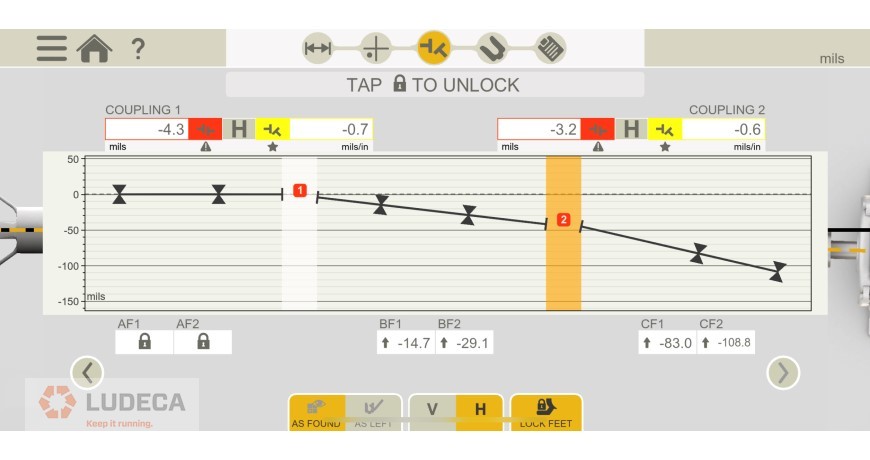

For example, while trying to make the horizontal corrections on the misalignment below, one may run into a bolt-bound situation on the far-right machine. Moving the back feet of the motor over 100 thousandths may not be possible.

However, by making all machines movable and letting the laser alignment system optimize the alignment moves, we now have achievable corrections at each pair of feet:

Notice that the back foot move of the motor on the far right dropped from an impossible 108.8 mils to a readily doable 11.9 mils.

Watch our Shaft Alignment Know-How: Bolt-Bound video to learn about the options of achieving alignment when in a bolt-bound or base-bound condition.

by Diana Pereda

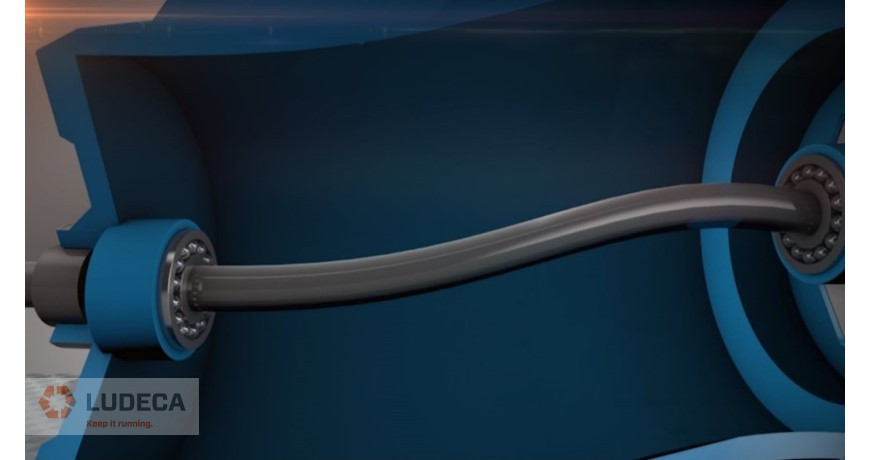

When performing shaft alignment, the alignment is typically measured by rotating both shafts at the same time. Why is this? The reason is that the coupling is already installed, so it is convenient to do. The other reason is that rotating both shafts is the only way to measure the true rotating centerline of the shaft. Not doing so results in measuring only the surface alignment, which is subject to surface finish imperfections, shaft straightness, and hub concentricity issues.

When should you remove the coupling for an alignment? For starters, you typically need to rough-align a machine before installing a coupling. This can be carried out with a laser alignment system. Another situation is for machines that are difficult to turn with the coupling in place, which requires removing the coupling in order to take a measurement. Finally, some machines have shafts that are coupled through fluid drives, so rotating both shafts simultaneously could prove very difficult.

Uncoupled measurements are very similar to coupled measurements. The goal is to make sure the shafts are at the same rotational angle when a measurement is taken. To make this task easy, Easy-Laser implemented a digital readout of the angle on each sensor in all XT series shaft alignment systems. I have found this invaluable for performing an uncoupled alignment. One simply needs to rotate one shaft to a determined degree and simply look at the sensor to match both shafts to the same rotational angle; once this is carried out, a measurement can be taken.

Some uncoupled alignments are made difficult with a shaft that is hard to turn or requires a turning gear that does not allow manually matching the shafts’ rotational angles together. To greatly simplify this task, Easy-Laser has included an “uncoupled sweep” measurement mode. This mode allows the user to turn one shaft so the laser beam will sweep by the first sensor, and then turn the other shaft so that the sensor will sweep past the laser again. This sweeping motion causes a point to be automatically taken for each time the sensors sweep past each other.

Related Blog: Uncoupled Misalignment Measurement Made Easy

by Diana Pereda

The Problem:

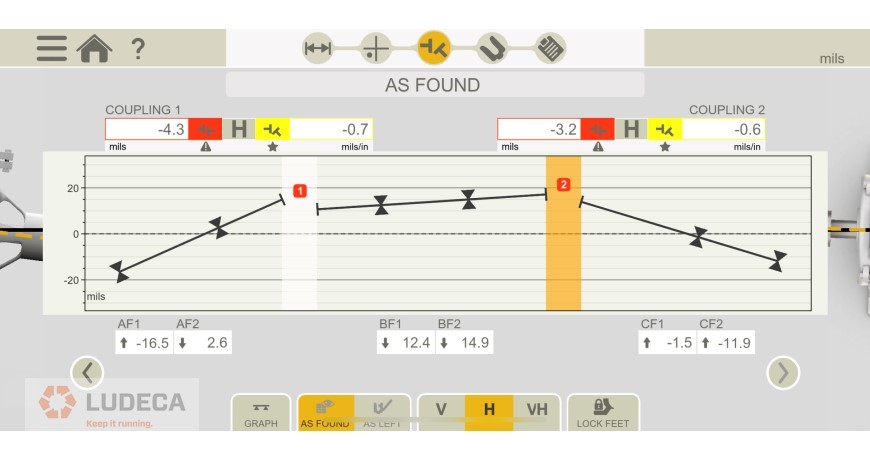

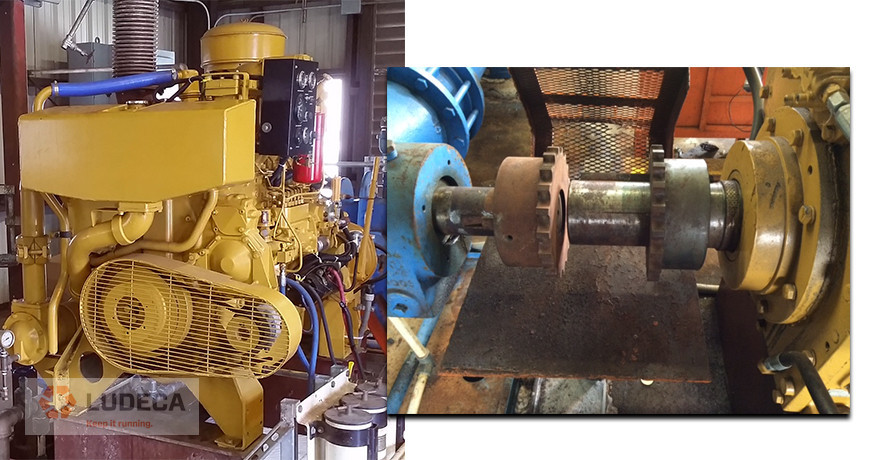

The customer complained of excessive vibration on a wastewater pump driven by a diesel engine. Upon performing an alignment check, the machine shafts were found to be grossly misaligned. Furthermore, proper alignment was found to be impeded by a base-bound condition of the engine combined with external horizontal forces caused by the exhaust stack.

The Solution:

A base-bound situation means a machine must be lowered to bring it into alignment but insufficient shims are present under the feet that must be lowered to permit removing them in order to achieve the alignment correction. Using an Easy-Laser XT770 laser shaft alignment system, it was easy to determine alternative possible corrections to overcome the base-bound condition. Horizontal alignment was also achieved using the graphical display of machine shafts and the live-move mode of the alignment system.

Savings:

Easy-Laser XT770 made it possible to find positive (instead of negative) shim corrections to immediately achieve alignment to within tolerance. This meant that enormous time and expense were saved by not having to disconnect and remove the engine, as well as hire a machinist and portable milling machine to mill down the base-plate of the engine.

Watch our Shaft Alignment Know-How: Bolt-Bound motion graphic video to learn about the options of achieving alignment when in a bolt-bound or base-bound condition.

by Diana Pereda

The following tips are ideas to consider for when “the going gets tough”, meaning that problems like residual soft foot, “bad geometry”, or becoming bolt-bound impede your ability to easily obtain an excellent alignment. But first, a few definitions:

- Residual soft foot: More soft foot than you are comfortable with, but can’t do anything about. Can be caused by problems like slightly angled feet or a bit of pipe strain.

- Bad geometry: Equipment where the distance from the coupling center to the front feet is equal to or greater than the distance from the front feet to the back feet.

- Becoming bolt-bound or base-bound: When alignment corrections can’t be made because you have run out of room in the anchor bolt holes in the feet, or have to come down but have no shims left under the feet to remove.

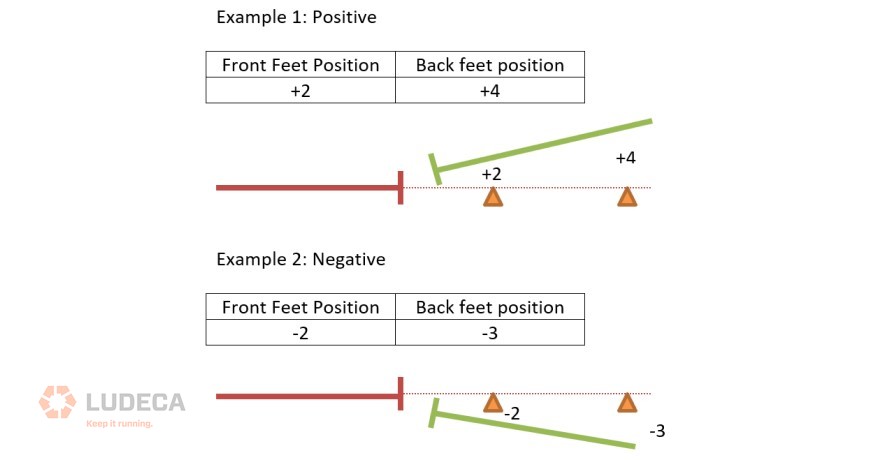

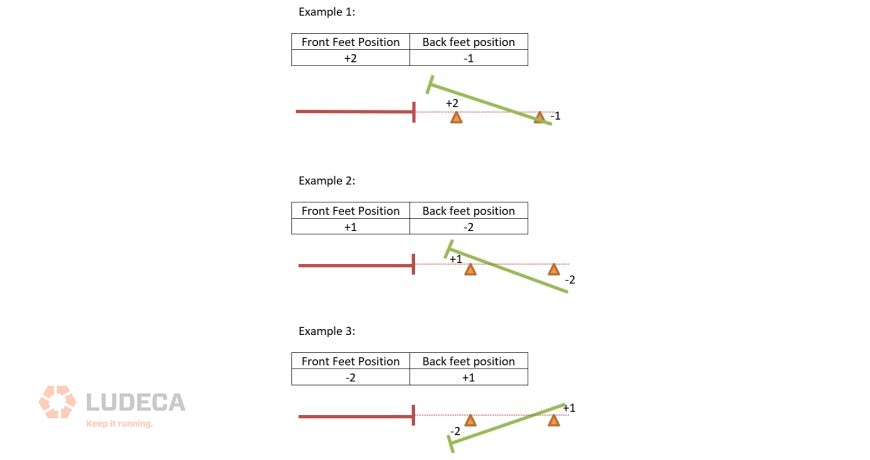

Final Vertical Misalignment Correction (Horizontal Misalignment already close)

1. Position front feet close to offset tolerance. Finish the alignment by moving the rear feet only.

2. Final foot positioning should make offset at the coupling center decrease. To achieve this, position feet as shown in the below example:

3. One must avoid leaving feet positioned with opposite signs, even if the values are very small. Below is an example:

4. One must also avoid allowing the position value of the front feet to be higher than the back feet value, even if they have the same sign. Shown below.

Notes:

- The above rules apply to horizontal corrections as well.

- Remember to torque the anchor bolts on small equipment in steps.

Watch our Shaft Alignment Know-How: What’s Misalignment video to learn the causes and effects of having misalignment in your rotating equipment.

by Diana Pereda

I’m a potential failure! I am the result of improper equipment design, procurement, installation, maintenance, and operation. I exist under extreme conditions for which I was never designed. I haven’t hidden or been silent, but most have ignored me and all have allowed me to grow. I’ll become a risk of severe damage and injury.

One day I will reach my full potential and show everyone what a failure I have become. At that moment, everyone will wish I had been given the early attention and mitigation I deserved.

Don’t feel sorry for me, because I am not alone, and will most likely return. I have created many other potential failures like myself. Some of those failures will cause even more harm and damage. Most likely, I will be reborn on the same equipment again and again due to improper maintenance practices.

If this does not concern you, then do nothing and let me show you what an equipment failure can really cost you when you least expect it and didn’t prepare for it. If you don’t like having me around, then what can you do? Here are some activities your maintenance and engineering departments can perform to prevent me from happening and ensure your equipment is operational upon demand, meaning reliable:

- Design for reliability

- Design for maintainability

- Design for operability

- Manage maintenance backlog

- Plan work, then schedule it and finally ensure it is properly executed

- Focus on PdM activities like vibration monitoring, IR thermography, lubrication analysis, and many more as a routine exercise

- Ensure precision maintenance is routinely done

- Perform operator checks

- Maintain properly written and continually optimized preventative maintenance activities that return value

- Provide training for operators, mechanics, and engineers to help ensure precision maintenance, proper operation, and reliable design

- Perform root cause analysis

- Ensure failure modes and effects analysis is a routine part of your maintenance and reliability efforts

- Ensure that you have identified all critical assets

- Ensure you have mitigation plans in place to deal with critical equipment failures

- Ensure that critical spare parts are available, properly stored, and easily accessible when needed

Visit our Knowledge Center for resources and tools to help you succeed when implementing and using our maintenance technologies! Watch our video tutorials, download infographics, plus explore other helpful information to reduce equipment failures and downtime.

by Diana Pereda

In general, laser shaft alignment systems have increased the ability to eliminate misalignment defects. There are many systems on the market, with varying capabilities, but the core benefit has been that the computer and laser work together to create an alignment report that can be used to assess and determine corrective action.

With advances in the interface and measurement technology, the skill required to take measurements has been reduced when compared to older methods, such as dial indicators. Thus, more users can perform the job with less training for the task of gathering the measurements. Unfortunately, this convenience has in some cases resulted in the good practices of the fundamentals of shaft alignment falling by the wayside, given the perceived ease of use. It has gone so far that some systems have marketed the idea that alignment can be done faster and in fewer and fewer steps to the point of rough alignment not even being necessary!

Is rough alignment not necessary?!?!

The claim is that if the laser can measure the misalignment without the laser going outside the detector, the alignment can be determined and the entire correction is done once. Anyone who has done at least one alignment in the field knows that this is far from the truth as you can’t escape physics in shaft alignment.

Depending on the setup, dial indicators could measure far more misalignment than a laser setup. Let’s say you had a situation where the indicators showed 300 thou misalignment. If you performed the right calculation would you expect to move the machine one time and get it within tolerance? Absolutely not! The reason is that the two shafts would be so strained as to the force required to bring the machines back together, that the coupling would be impossible to install, the shaft would deflect, and the forces would cause incorrect soft foot measurements. Again, you can’t escape physics.

The solution is to rough align the machine! It’s a best practice as per our field-proven 5-Step Shaft Alignment Procedure, which applies to all shaft alignment tools.

What about measuring severe out-of-alignment conditions with a laser alignment system?

First of all, if you are aligning an existing machine that has been running and did not experience a failure, I will give the previous alignment technician the benefit of the doubt that it was not severely out of alignment, and 99% of the time, you will not encounter the laser going out of the detector.

Second, if it is a rough alignment there is a chance it could move out of alignment for any laser shaft alignment system, single or dual beam. In rough alignment, you will typically align with a straight edge and most likely be within laser detector range to get an approximate set of readings. In one case, I checked the rough alignment of the machine with a 27-foot separation between machines (shown below.)

The lasers moved 8″ from the detector on both sides. Regardless of whether you had a single beam or a dual-beam system, there is no system on the market with a detector that is 8″ in size to handle this rough alignment, nor is it necessary, provided you have a dual laser beam type laser alignment system.

How do you rough align with a laser alignment system?

Fortunately, I used the Easy-Laser XT770 which features a dual laser configuration. Using a process called “coning” I was able to rotate both shafts from 90 to 270 degrees, move lasers to the middle of travel and then use them as a visual indicator to align the machines until both lasers hit the center of both detectors. In one vertical and horizontal movement, like magic, the axes of rotation were rough aligned. The millwrights on hand were amazed at how quick, efficient and intuitive this method was – which can only be done with a dual laser alignment system. This means the machines were roughly aligned 27 feet apart without dealing with a complicated movement of the laser during measurement as the single laser systems require. We were then able to do a full 360-degree measurement, get the values, and start the alignment corrections and finish the alignment as per the 5-Step shaft alignment procedure.

Related Blog: Benefits of Performing a Rough or Initial Soft Foot in an Overall Alignment Procedure

by Diana Pereda

We welcome you to read the previous blog in this series, “What is Machine Train Alignment and How Important Is It? Part 2”

ANALYSIS 2: THE REFERENCE MACHINE IN THE TRAIN CANNOT BE MOVED

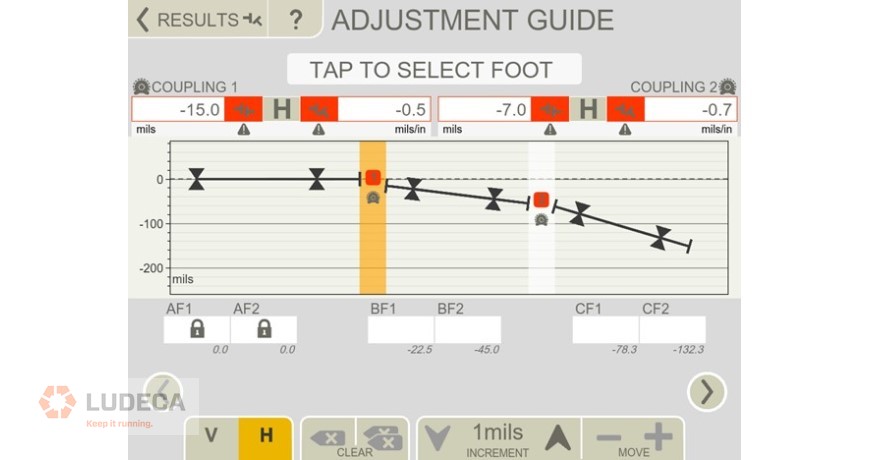

Now we have to face the situation of the big 172 mils moves at DF2, Compressor 3 back foot. For this, we are going to make use of the XT770 Adjustment Guide to predict what will be the minimum moves needed at Compressors 1, 2, and 3 to get the misalignment to excellent tolerances.

Here is a brief description of what is the Adjustment Guide and how it works:

It is Firmware utility built into the Easy-Laser XT770 alignment system to aid the aligner to predict what will be the minimum moves or shim changes required to align all the machines in the train to get the alignment at each coupling within tolerance when there are limitations to adjustment such as when Machine 1 cannot be moved in a 3-or more machine train. Let’s explore what can be done in our alignment.

As stated in Blog1 the calculated corrections at Machines 2, 3, and 4 are to bring the whole train to alignment to Machine 1. We also spoke on how valuable this information is.

Now that we know ‘the whole picture’ of the train and we know that Machine 1 cannot be moved, we can make ‘virtual moves’ and predict the minimum required moves at each pair of machine feet to get the alignment between consecutive machines to excellent tolerances. See examples in pictures 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13.

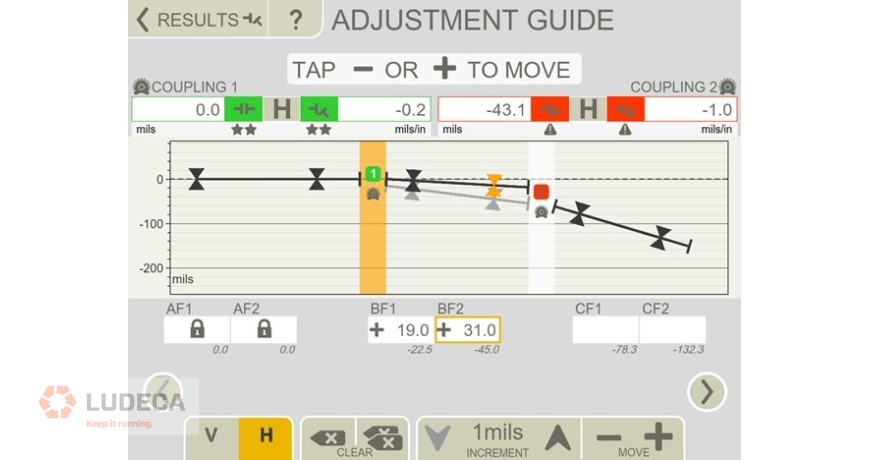

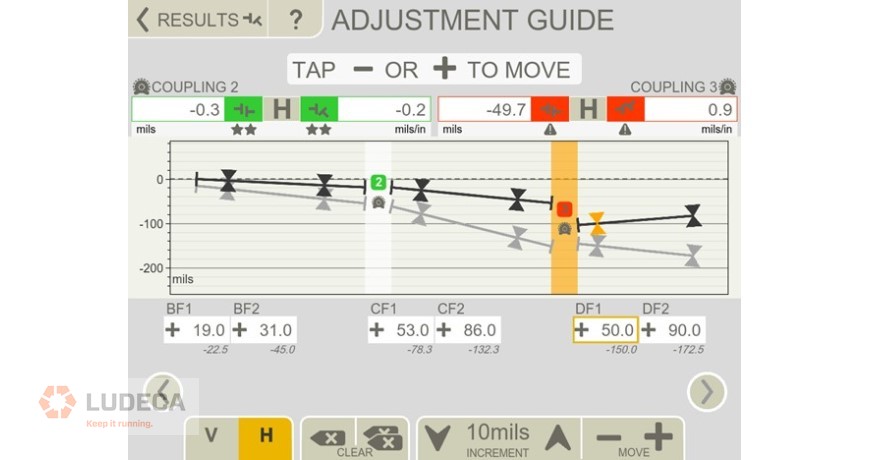

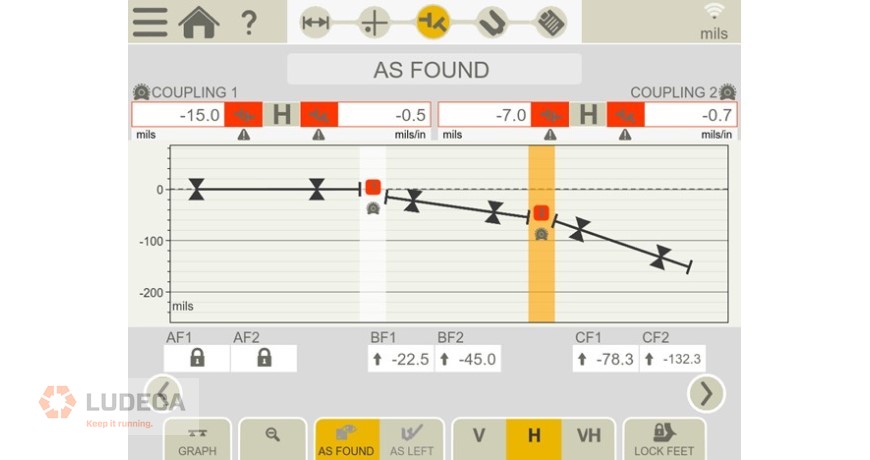

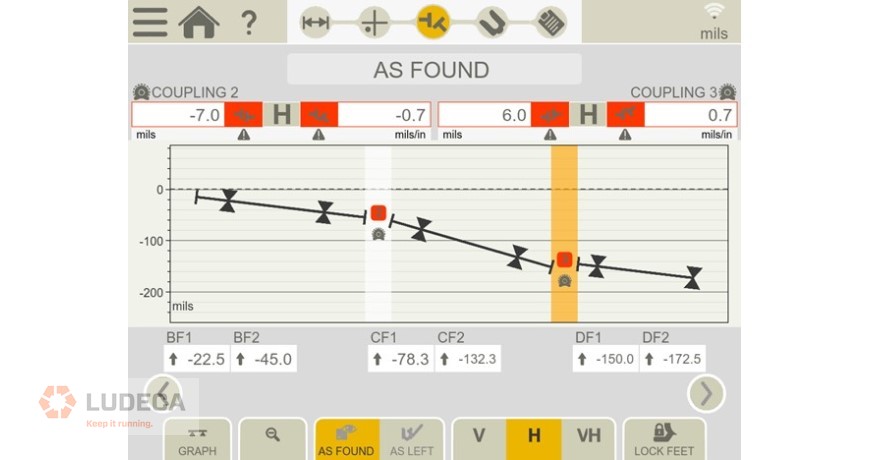

When we first invoke the Adjustment Guide we see a graph pictured below.

Allow me to describe what we are looking at in Picture 7. Several things:

- The actual misalignment at couplings 1 and 2.

- Machine 1 feet, AF1 and AF2 are ‘Locked’ because they cannot be moved.

- We see empty white rectangular boxes under BF1, BF2, CF1, and CF2.

- Underneath the white rectangles, we see the needed adjustments to make to bring machines 2 and 3 into alignment with Machine 1.

- We see the interval set up, set to 1 mils by default, and of course adjustable up to 125 mil increments every time you press the + or – icon. In other words, user-adjustable to save time.

- The left and right arrows allow the user to move down or up on the machine train.

Having said this, we used the arrows to ‘virtually move’ BF1 and BF2, see below.

Picture 8 shows the final virtual adjustment on BF1 and BF2 to get Machine 2 to ‘Excellent’ alignment relative to Machine 1. Please note a couple of things:

- We needed to move machine 2 only 19 mils at BF1 and 31 mils at BF2 instead of 22.5 mils and 45 mils to get to excellent alignment. And more importantly…

- It allows us to leave the angularity of machine 2 with an angle such that machine 2 ‘points towards machine 3’, thus minimizing the moves at machine 3 to get it to perfect alignment with Machine 2.

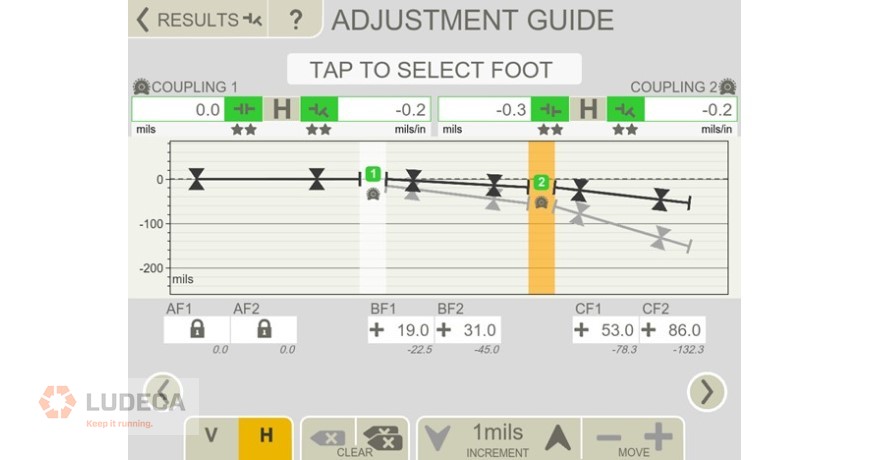

Picture 9 above shows the ‘virtual moves’ needed at CF1 and CF2 to get Machine 3 aligned to excellent tolerances with respect to Machine 2.

Please note that to achieve Excellent alignment the move at CF1 is only 53 mils instead of 78.3 mils and at CF2 it is 86 mils instead of 132.3 mils. Also note that we left Machine 3’s angularity in such a way that Machine 3 points towards Machine 4, thus minimizing the moves that will be required at Machine 4.

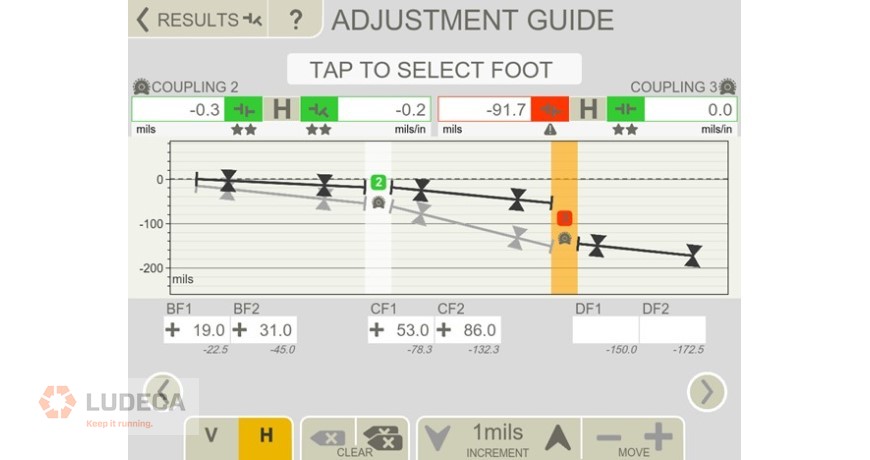

Picture 10 below shows the last 2 couplings and DF1 and DF2 with ‘empty’ values.

Underneath the empty rectangles that are waiting for the input of the virtual moves, we see the required move to bring Machine 4 (Compressor 3) into alignment with Machine 1, which are, DF1 150 mils and DF2 172.5 mils. However; what is needed, as pointed out before, is only to bring Machine 4 into alignment with Machine 3, not with machine 1. See Picture 10 below.

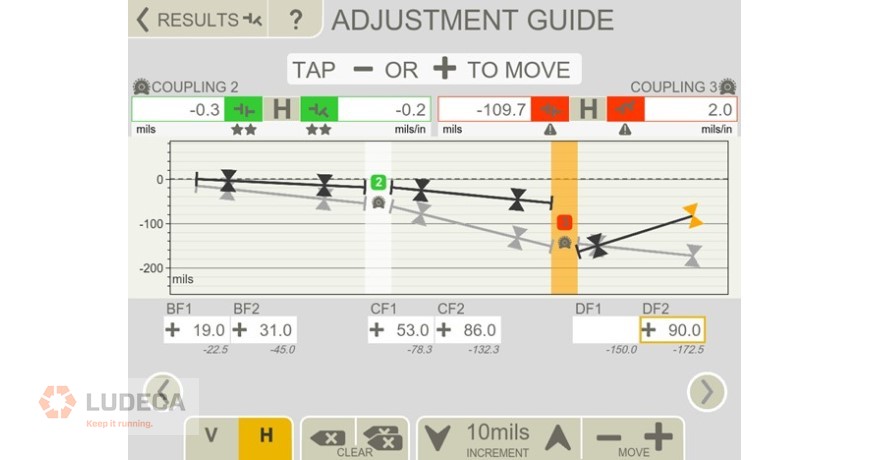

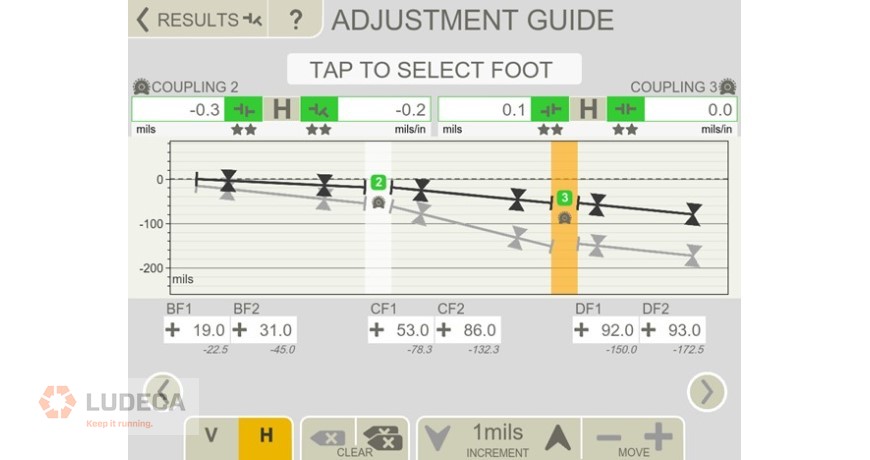

We continue the process as we did before making ‘Virtual Moves’ at DF1 and DF2 in any order until excellent alignment is achieved. See Picture 11 below.

Picture 11 shows that we have ‘Virtually Moved’ DF2 90 mils.

We will proceed to move DF1 and DF2 in any order until we reach excellent alignment. Remember the ‘increment’ is adjustable, hence when getting close to alignment it can be lowered to 1 mil to make more precise moves.

Picture 12 shows that we have moved DF1 50 mils and DF2 90 mils.

Picture 13 shows the moves required at DF1 to be only 92 mils instead of 150 mils and for DF2 only 93 mils instead of 172.5 mils to achieve alignment to tolerance.

As we can see, the Adjustment Guide utility is a tremendous aid that helps the aligner predict what is going to happen and most importantly find out if he or she will be able to obtain his or her goal.

by Diana Pereda

Shaft Alignment is a critical step in any world-class maintenance program, and when done properly, can help decrease unscheduled downtime and keep equipment running longer and more efficiently. This means machines need to be aligned within the recommended tolerances based on the RPM of the equipment. However, this is sometimes easier said than done, especially if any residual soft foot is present, or due to bad geometry in the movable piece of equipment. If you find yourself struggling to complete an alignment to tolerance, here are some tips that, when combined with Ludeca’s 5-Step Shaft Alignment Procedure, may help you complete the alignment faster and with less frustration.

- Get the position of the front feet close to the alignment offset tolerance. Once the front feet are close to or within the tolerance value, complete the alignment by correcting the rear feet only.

- Try to leave both the front and rear sets of feet with positions having the same sign, either positive or negative.

- It is not desirable to leave the position value of the front feet higher than the position value of the back feet. This means that the final position value of the rear feet should be larger in value than the position of the front feet.

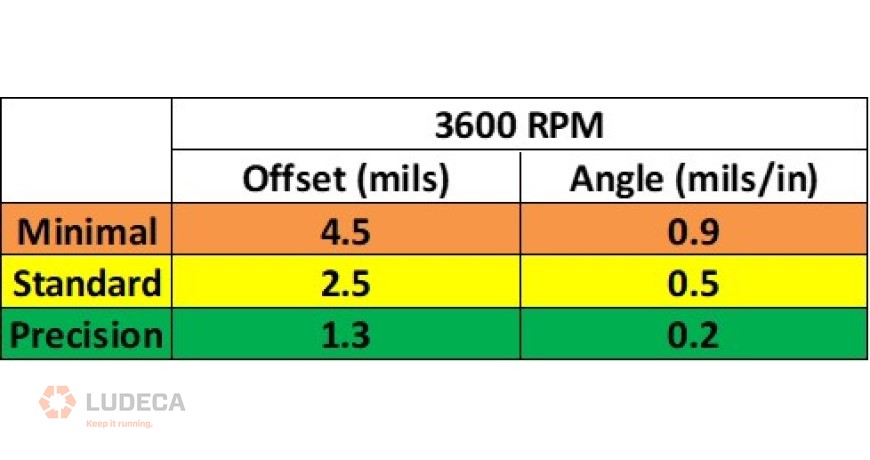

The following scenario is an example of how these rules can be applied to help you complete an alignment to precision tolerance as defined by the ANSI standard (ANSI/ASA S2.75-2017/Part 1.) This standard defines three acceptance levels: Minimal, Standard, and Precision. These acceptance levels, as well as the corresponding tolerance values for 3600 RPM, are shown below in Figure 1. The scenario below was prepared utilizing an Easy-Laser® XT770 Shaft Alignment System and the Adjustment Guide feature. Our Easy-Laser XT Series is one of the few laser alignment platforms on the market today with the new ANSI alignment tolerances built-in giving the user the freedom to choose between traditional tolerances, the new ANSI standards, or custom tolerances.

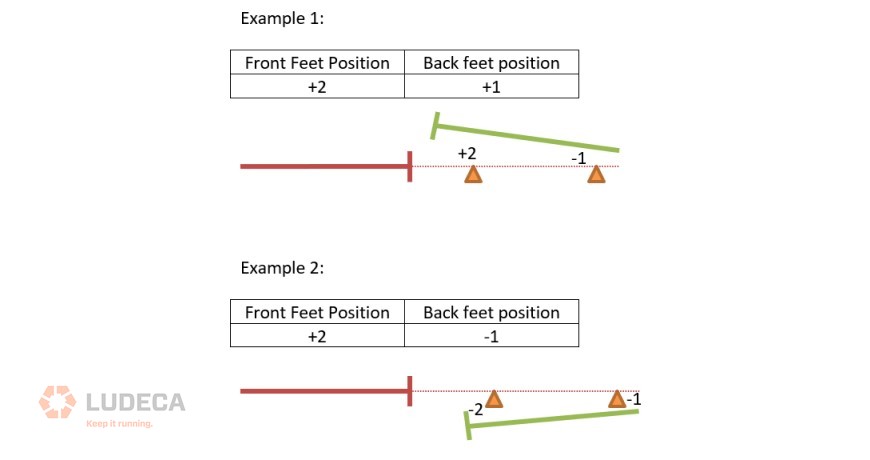

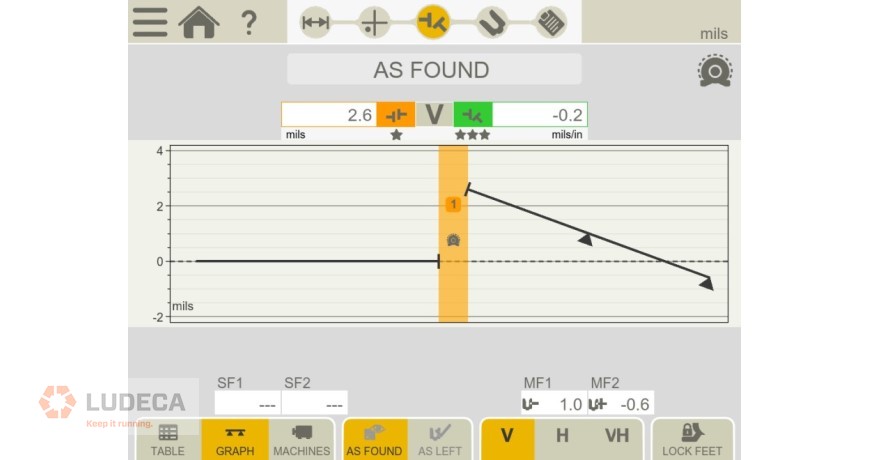

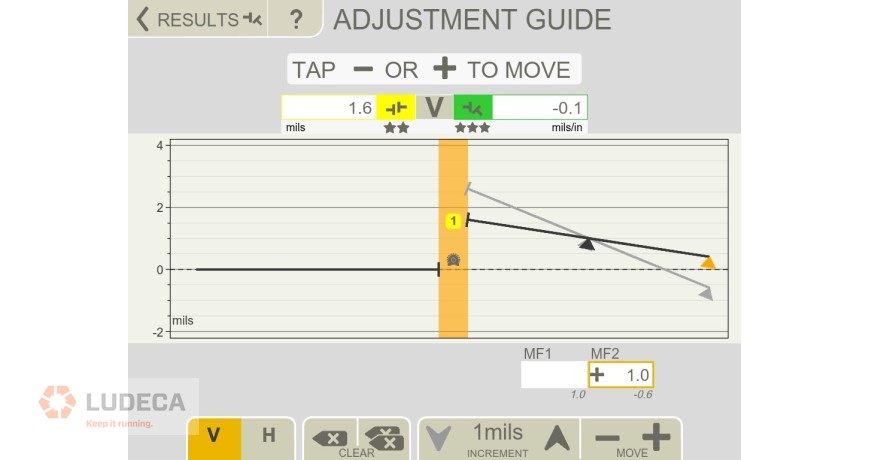

In Figure 2 we have our shaft alignment results measured on equipment running at 3600 RPM, where the position of the front feet is at +1.0 mils and the position of the rear feet is at –0.6 mils. This creates misalignment at the coupling with an offset measuring +2.6 mils, which puts us in the Minimal tolerance range. We need to make some adjustments to improve the alignment in order to reach the precision tolerance range, but how? Let’s try following the recommended tips!

If we look at the position of the front feet in Figure 2 we see that we are at +1.0 or 1.0 mils too high. Since the position of the front foot is already less than the desired Precision Offset Tolerance Value of ±1.3 mils (shown in Figure 1), Tip 1 says we should leave the front feet where they are and complete the alignment by correcting the rear feet only. Looking at the position of the rear feet in Figure 2, we see that we are at –0.6 or low by 0.6 mils. Using the Adjustment Guide feature on the XT770, let’s see what would happen if we add 1 mil worth of shims to the rear feet.

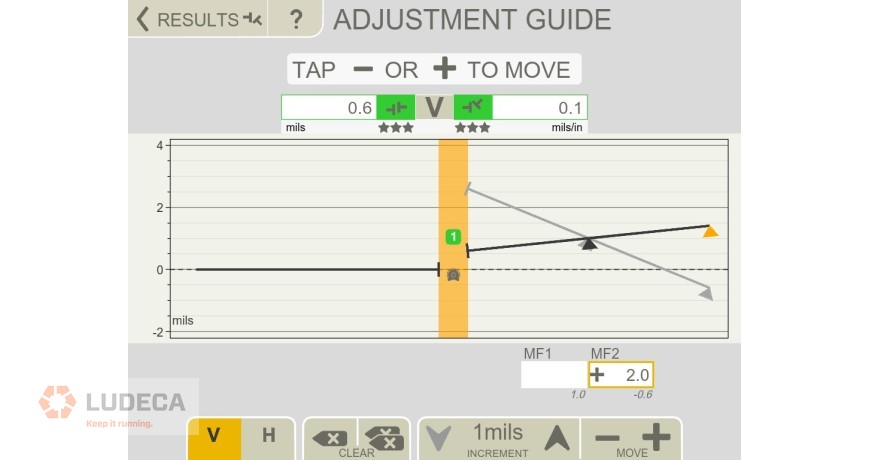

In Figure 3, we add 1 mil of shims to the rear feet of the alignment result that was shown in Figure 2 bringing the new position of the rear feet to +0.4 mils with the front feet still at +1.0 mils. Although both feet now have the same sign, satisfying Tip 2, we see that this still produces an offset measuring 1.5 mils at the coupling, putting us within the Standard alignment tolerance range. Although we did improve the alignment slightly, we still are outside of the Precision alignment tolerance that we are pursuing. What would happen if we added another 1 mil to the rear set of feet bringing the final position of the rear feet to +1.4 mils?

Now in Figure 4, we have added 2 mils worth of shims to the rear feet of the alignment result that was shown in Figure 2, bringing the final position of the rear feet to +1.4 mils with the front feet still at +1.0 mils. Now we see that the position of both the front and rear sets of feet are positive in value satisfying Tip 2. Additionally, the positional value of the rear feet is greater than the positional value of the front feet, thereby also satisfying Tip 3. Now if we look at the misalignment measured at the coupling, we have an offset measuring just 0.6 mils and putting us well within the desired Precision alignment tolerance. In addition, the angularity value has also decreased and is well within the precision alignment tolerance range. Note also that adding shims is always easier than removing them, especially if you do not have enough thickness of shims left under the feet to make the desired negative correction possible.

We hope these three tips will make your task of precision aligning machines much easier.

Request your complimentary copy of our Shaft Alignment Fundamentals Wall Chart which highlights the ANSI/ASA Shaft Alignment Tolerances as well as information and guidelines for the implementation of good shaft alignment of rotating machinery, best practices, soft foot, tolerances, thermal growth, and much more!

by Diana Pereda

We welcome you to read the previous blog in this series, “What is Machine Train Alignment and How Important Is It? Part 1”

ANALYSIS 1: ALL MACHINES IN THE TRAIN CAN BE MOVED

Since ALL 4 machines in the train can be moved we have many options.

Option 1:

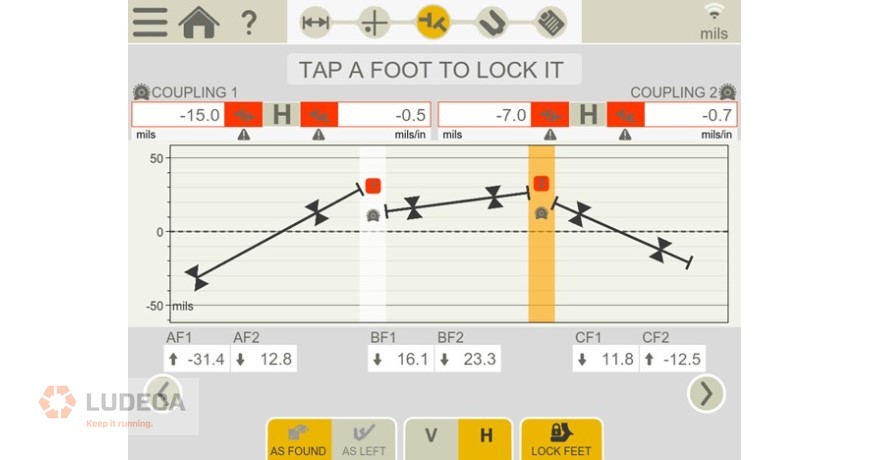

Let’s see what the minimum moves will be for the whole train. How we do that with the Easy-Laser XT770? We simply make ALL 8 feet in the train movable. NO LOCKED FEET in the train. See Picture 3 and Picture 4 below.

What can we conclude from those two pictures? A couple of things:

- What we see in the graphs is what we call: ‘The Optimized Alignment Line’. Simply the XT770 finds the Alignment Line that will minimize ALL MOVES. The proof that we are looking at an Optimized Line is that the SUM of the Absolute Values of the Negative and Positive corrections (moves) is the same. In those pictures, we see that the Negative Values add to 64 mils and the Positive Values add to 64 mils.

- We see that the big 172 mils move at DF2 is now only 6.4 mils.

- We also see that the biggest move in the train is at AF1 (Turbine Back Foot) only 31 mils.

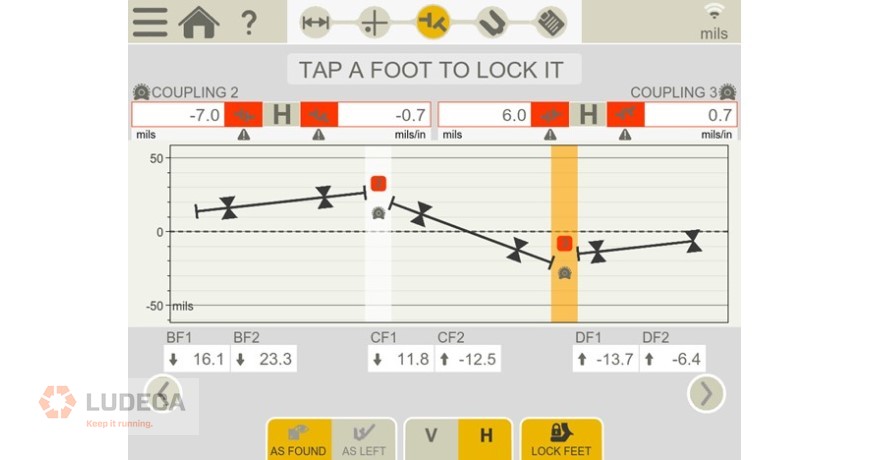

Option 2:

For example, we can explore if we can minimize the Turbine move. The XT770 allows you to ‘Lock’ any feet. We Locked AF1, which was the biggest move in the Optimized view, and CF1 arbitrarily. See Pictures 5 and 6 below.

The XT770 calculates the moves for the remaining feet you are to move. As you see, not a bad option but not as good as moving both Turbine feet.

As mentioned above, in addition to moving ALL feet you can ‘Lock’ any feet to be able to analyze the best option. Going through all the possible combinations will make this blog extremely long torture for the reader.

by Diana Pereda

Do your washers resemble cones?

If so, you could be falling victim to a common headache experienced in some shaft alignment jobs. What could mistakenly be diagnosed as soft foot or coupling strain, “dished” or “cupped” washers center themselves in the feet causing the machine you are aligning to move laterally as you tighten the hold-down bolts. Prevent this from happening by performing pre-alignment checks and replacing any washers that exhibit this defect. Also, check the surface of the machine feet for similar grooves that have been cut by washers in the past. These grooves can also cause this effect and make your alignments challenging.

Related Blog: The Impact of Washers on Shaft Alignment

by Diana Pereda

What is Machine Train Alignment?

Machine Train Alignment is a multi-coupling alignment where two or more consecutive machines can be adjusted.

For example, a 3-coupling train (4 machines), such as a Gas Turbine driving 3 Compressors.

NOTE: A 2-coupling (3 machine) train such as a Pump–Gearbox–Motor, where the Gearbox in the middle is determined to be NON-movable, is NOT a Machine Train; it could be treated as one but that is not the best option. It is best to treat this as two separate alignments using the Gearbox as the ‘Stationary Machine’. In one alignment, align the Pump to the Gear-Box, and in the other, align the Motor to the Gear-Box.

NOTE: Normally, most laser shaft alignment tools will use the first machine on one end of the train, say the left machine, as the Reference Machine, and after collecting the data at all couplings the alignment tool will combine all the misalignment values to calculate the required moves to align ALL the machines in the train to the original reference (alignment line), in most cases machine number ONE.

Is this the goal we are trying to achieve? NO! We are trying to align two machines next to each other. Then, what is the value of the machine train program? A TREMENDOUS VALUE, as it gives the aligner “the Overall Picture” of how all the machines sit with respect to the reference line and therefore also how they sit with respect to each other. Why do we need to know this? Because we need to avoid getting ‘Bolt Bound’ or ‘Base-Bound’.

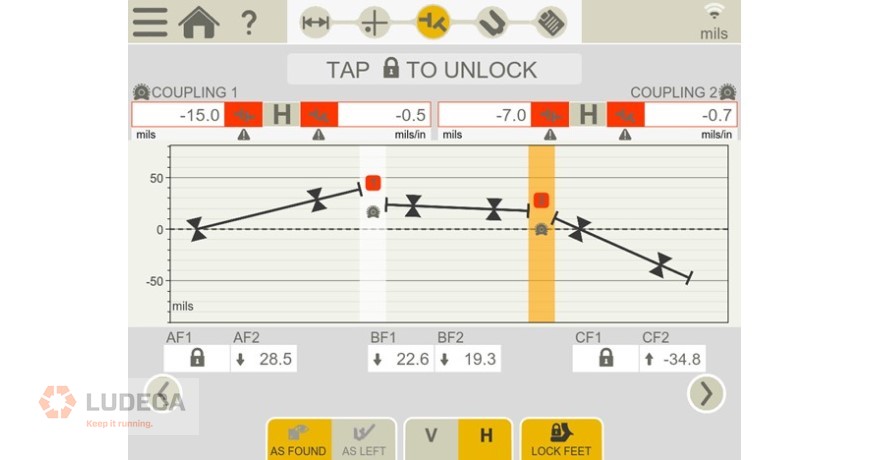

We will use an Easy-Laser XT 770 Laser Shaft Alignment tool with data collected in a 4 machine train (3 coupling) for this blog. In a four-machine train, after reading the misalignment at each of the three couplings, we found the following Horizontal Misalignment values versus the entered Misalignment Targets that were desired. See Pictures 1 and 2 below.

What we observe in Picture 1 is a laser alignment tool depicting the first TWO couplings (3 machines) in the THREE coupling train. We see that the first machine is the reference (Stationary Machine), we observe both the misalignment at couplings 1 and 2, and the required Horizontal Moves to align machine number TWO (BF1 and BF2 moves) and machine number 3 (CF1 and CF2 moves) to the reference machine number 1. We begin to see a big move at CF2, 132 mils (Thou). CF2 is the Compressor #2 Back Foot.

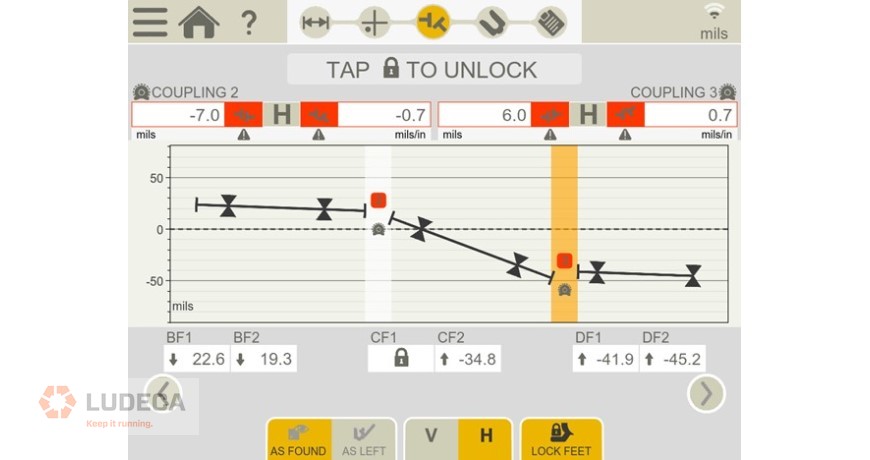

What we observe in Picture 2 is the misalignment at couplings 2 and 3 and the required corrections to bring all THREE machines to Machine ONE, the original reference (Alignment Line). See a possible problem now? Do you think we will be able to move DF2 172 mils (Thou)? DF2 is the Compressor 3 Back Foot.

In my next blog, we will then see how easily we can analyze and solve the apparent bad situation we are facing.

NOTE: Please realize that the pictures you saw are ‘GRAPHS TO SCALE’ of the misalignment. Observe the scale on the left side of the graphs.

by Diana Pereda