Introduction

Large commercial chillers are the backbone of many facilities, supplying thousands of tons of cooling through extensive piping networks. But even when the equipment itself is built to last, the structures that support it may not be.

During routine vibration data collection, our team identified excessive vibration not on the chiller, but on the piping support structure tied into the system. Follow-up testing confirmed the cause: resonance. This wasn’t a threat to the chiller itself, but to the facility structures that keep the chilled water system in service.

The Setup

The facility operates six chillers connected to a common chilled water header. The newest unit, a Trane 862 kW (≈1,156 HP) chiller operating at 4160 V and 3570 RPM, was piped into the header alongside the existing chillers. The chilled water lines are supported on heavy H-beam steel mounts.

While the supports appeared substantial, vibration monitoring revealed otherwise.

The Discovery

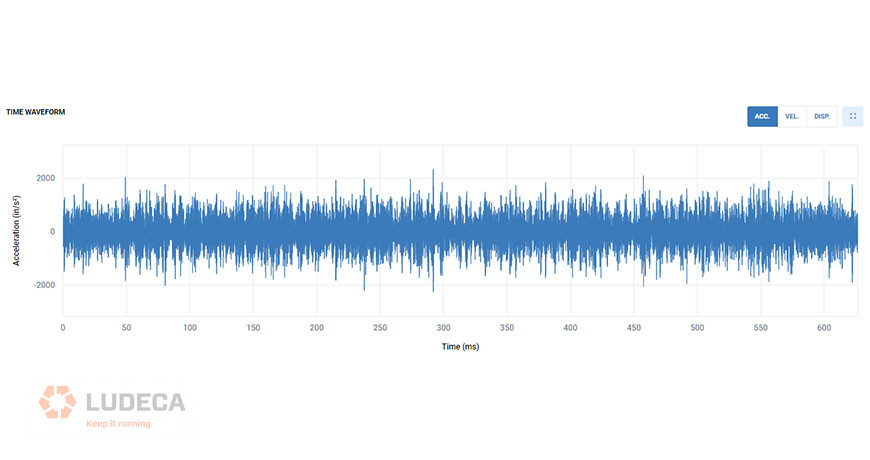

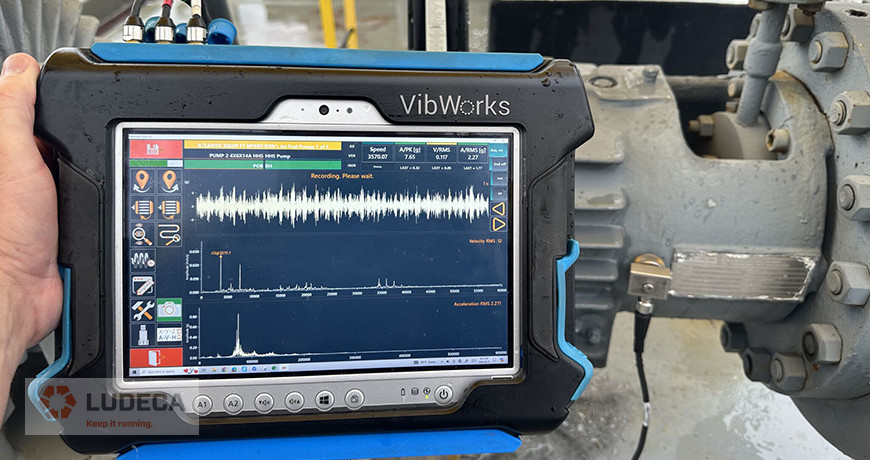

Routine data collection was performed with a Betavib King vibration analyzer using a TREA330 premium CTC Triax accelerometer, along with CTC cables and magnets.

The analyzer showed that while the chiller itself was operating normally, the piping supports were vibrating excessively. This triggered a deeper investigation.

To confirm the root cause, we conducted impact testing using the same Betavib analyzer with a single CTC AC192-1D accelerometer. The results showed that the H-beam supports had a natural frequency of ~59–60 Hz — nearly identical to the chiller motor’s operating speed of 3570 RPM (59.5 Hz).

When the chiller was online, vibration at the top of the support frame reached about 0.7 in/s peak at 1× running speed. Amplitudes increased from bottom to top, showing that the structure was resonating in its first bending mode.

Why Resonance Matters

It’s important to understand: the chiller itself was not in danger. Rotating equipment is designed to operate at 3570 RPM continuously.

The real risk lies in the facility structures being forced to vibrate at that same frequency. At 0.7 in/s peak, the piping supports were experiencing vibration levels high enough to cause long-term structural problems if left uncorrected.

This level of motion, repeated 60 times per second, can lead to:

- Piping chafing against the steel mounts, wearing through insulation, coatings, and eventually the pipe wall

- The risk of a hole in chilled water piping, leading to a catastrophic facility flood

- Fatigue cracks in welds and anchors

- Loosened hangers and piping supports

- Leaks at flanges and nozzle connections

“It’s not the chiller that fails — it’s the facility around it.”

Mitigation Strategies

To protect the facility, corrective actions must address the structural resonance:

- Stiffen the support structure — add gussets, cross-bracing, or tie-backs to raise the natural frequency above ~75 Hz.

- Add damping — apply constrained-layer damping or viscoelastic pads to reduce peak response.

- Install a tuned mass damper (TMD) — placed near the top of the frame, tuned to ~60 Hz, to absorb vibration energy.

- Isolate the piping — with spring hangers or isolators (within nozzle load limits).

- Minimize excitation — alignment and balance checks can help, but the primary driver here was structural resonance.

Lessons Learned

This case highlights the value of routine vibration monitoring with professional-grade equipment. The Betavib King analyzer with CTC Triax sensors identified the abnormal piping vibration that visual inspection could not. Follow-up impact testing with the CTC AC192-1D accelerometer confirmed the resonance problem.

The key lesson: resonance doesn’t damage the chiller — it damages the facility around it.

To avoid that risk:

- Collect routine vibration data on both equipment and connected structures.

- Perform impact testing when abnormal motion is detected.

- Ensure piping supports are designed with natural frequencies well clear of motor running speeds and harmonics.

Conclusion

Routine data collection with the Betavib King analyzer revealed that the piping supports for a Trane chiller were resonating with its operating speed. Left uncorrected, this resonance could lead to pipe chafing, fatigue, and even a catastrophic flood — not because the chiller failed, but because the supporting structures could not withstand resonance.

By detecting the problem early, corrective action can be taken before the facility suffers costly downtime. As chillers grow larger and more powerful, vibration management must extend beyond the machines themselves to the structures that carry their loads.

Thank you Brian Franks with JetTech Mechanical LLC for sharing this informative article with us!

Understanding the consequences that resonance has on equipment reliability

by Diana Pereda

1. Introduction

A large number of condition monitoring (CM) programs fail—not because vibration monitoring is ineffective, but because managers and decision-makers lose confidence in the systems they install. Too often, these systems either fail to detect real faults or generate excessive false alarms.

The root cause is usually the same: organizations are misled by overpromises about limited solutions. Many believe that simply tracking overall vibration levels—such as:

- Acceleration Peak (Acc Peak)

- Acceleration RMS (Acc RMS)

- Overall Velocity RMS (per ISO standards)

is enough to guarantee the success of their investment. In practice, it is not. These indicators are quick to calculate, easy to trend, and provide a general overview of machine behavior. They are useful as first-level alarms, but on their own, they cannot ensure reliable fault detection.

After such disappointing trials, companies often become reluctant to reinvest, missing the opportunity to benefit from advanced monitoring.

This article is meant to clarify why simply “collecting vibration” is not the same as tracking every single change in dynamic behavior, and why relying only on overall levels inevitably leads to blind spots. By understanding these limitations, decision-makers can make informed choices about technologies that deliver real reliability and measurable return on investment.

2. The Mask Effect and Its Consequences

The mask effect occurs when one vibration source generates high amplitude and hides other components of the signal within the overall value. This can lead to a dangerous situation where the machine appears stable, while in reality new faults are developing.

Typical Scenarios of Masking:

- Dominant low-frequency phenomena: A strong unbalance at the shaft’s rotational frequency can dominate the overall RMS, masking misalignment, looseness, or early-stage bearing faults.

- High-frequency masking: When high-frequency components—such as gear mesh frequencies (GMF), bearing defect frequencies (BPFO/BPFI), or resonance excitations—are present, their high amplitude can increase the overall RMS tenfold. In such cases, the indicator becomes “blind” to changes in low or mid-frequency ranges.

- Resonance amplification: Structural resonances may generate very high peaks that saturate overall acceleration RMS, again hiding subtle changes in machine behavior.

As a result, overall levels cannot guarantee reliable fault separation or early detection, particularly when multiple phenomena coexist.

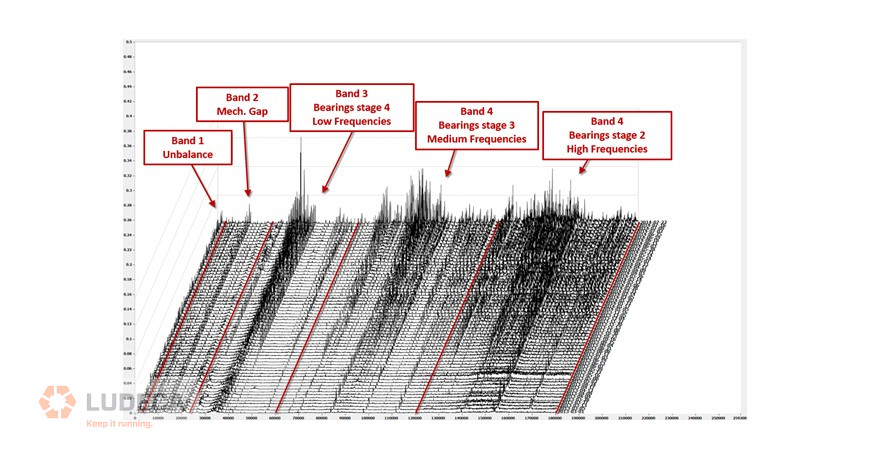

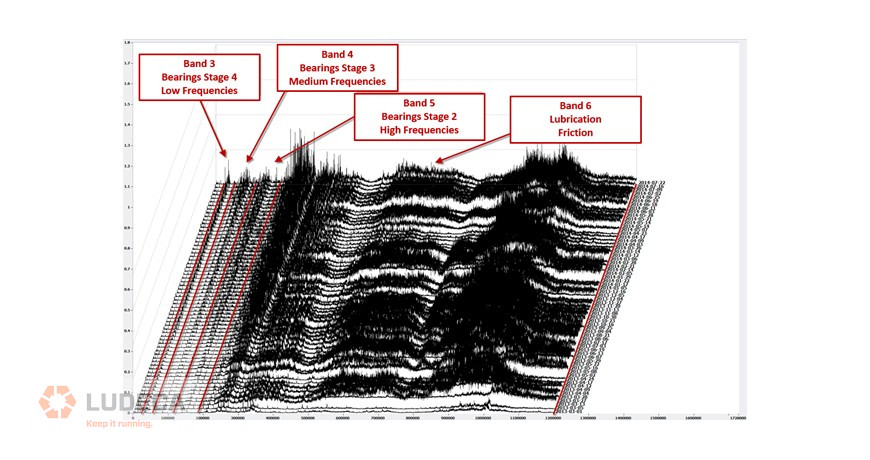

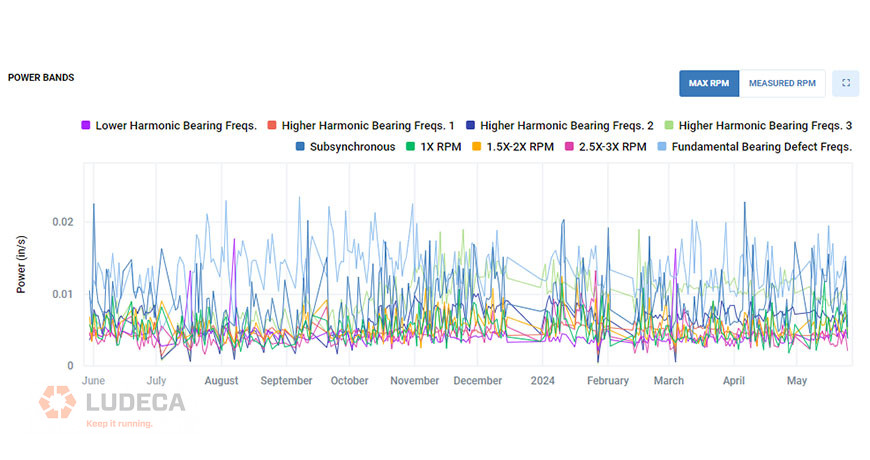

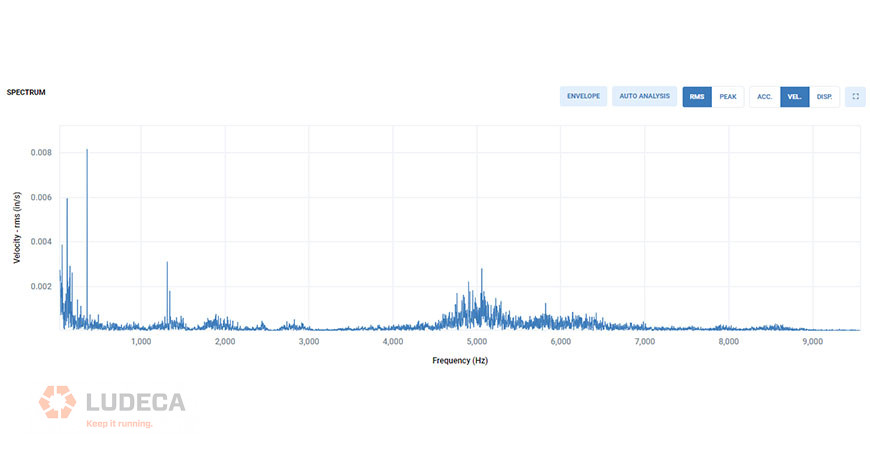

The following experimental data coming from real assets clearly demonstrates how standard overall vibration levels are not capable of detecting the change in the dynamic behavior of the monitored asset, not to mention detecting a health issue affecting the equipment.

While proper knowledge of the failure mechanism correlated with the right tools that VibWorks King is, it’s easier to notice that for the exact same machine and under the same timespan (6 years), the assets triggered danger levels 4 times, and was safely repaired during scheduled shutdowns.

3. The Right Solution: Power-in-Band Monitoring

Looking at overall RMS values is a bit like taking a photo with the wrong lens:

- If you only use a wide-angle lens, you capture the whole scene, but you miss the details—small cracks, fine textures, or subtle movements are invisible.

- Similarly, overall vibration levels (Acc Peak, Acc RMS, Velocity) give you the big picture of the machine, but they blur out the details of specific faults.

To truly understand what is happening inside the machine, you need the right focal length—the right “zoom” on the right part of the spectrum. This is exactly what power-in-band monitoring provides.

By splitting the vibration spectrum into a certain number of frequency bands, each “lens” focuses on a different fault mechanism:

- Unbalance Band – like zooming on the main subject (1× speed).

- Misalignment Band – the next focal range, catching distortions you’d miss with the naked eye.

- Mechanical Gaps Band – exposing looseness and coupling play hidden in the background.

- Bearings Low-Frequency Band – a macro lens for cracks and spalls appearing at low frequencies.

- Gear Mesh / Bearings High-Frequency Band – a telephoto lens capturing fine details of GMF and early bearing fatigue.

- Lubrication Band – a high-speed lens revealing subtle friction and micro-impacts invisible in a normal shot.

With this approach, each band acts like a dedicated lens for a specific phenomenon. No one effect can blur or hide another. You can “zoom in” on any change in dynamic behavior and capture a crisp picture of the machine’s condition.

4. Benefits of 6-Band Monitoring

By separating the vibration spectrum into these six bands, the monitoring system can:

- Isolate phenomena: Each physical defect mechanism is tracked independently (harmonics, shocks, friction, looseness, etc.).

- Eliminate masking: No single phenomenon can hide another—changes are visible even if overall RMS remains constant.

- Enable early detection: Slight variations in dynamic behavior are immediately identified.

- Improve reliability: Maintenance teams can intervene earlier, with clearer diagnostics and lower costs.

5. Conclusion

Overall vibration levels (Acc Peak, Acc RMS, Velocity ISO) are a convenient first step, but they are like a blurry snapshot—limited by the mask effect, especially when high-frequency components or resonances dominate.

The solution is power-in-bands monitoring, where each band acts as a dedicated lens focusing on a specific fault type. Instead of a single blurred picture, you get a complete professional photo album of the machine’s health: sharp, detailed, and unambiguous. This approach provides a full and reliable view of machine dynamics, eliminates blind spots, and enables confident, proactive maintenance decisions.

Thank you Betavib for sharing this valuable article with us!

4 Common Vibration Issues that are Easily Detected to Extend Equipment Reliability

by Diana Pereda

A shaft centerline diagram is a plot used in the vibration analysis of journal bearings. It is also called a shaft average centerline diagram. The purpose of this graph is to display the average position of the rotor in the bearing. In short, for different bearing types, there is an expected or “normal” position of the shaft in the bearing. If this position changes, it can indicate a problem.

Figure 1 above shows two mass-spring systems vibrating at the same amplitude and frequency. They are, however, vibrating around different points, (the horizontal dashed black lines.) You can think of the shaft centerline diagram as the point the shaft is vibrating around.

If the blue wave in the figure above was electricity, it would be an alternating current (AC). This is what the AC output of a vibration sensor would look like if it was measuring the vibration of the mass in the figure. If you look at the black dashed horizontal lines, this looks like direct current (DC) voltage. The proximity probes used to measure the shaft centerline diagram put out both an AC and DC component. Because we are interested in position rather than vibration in this plot, we only keep the DC component. This is called DC coupling.

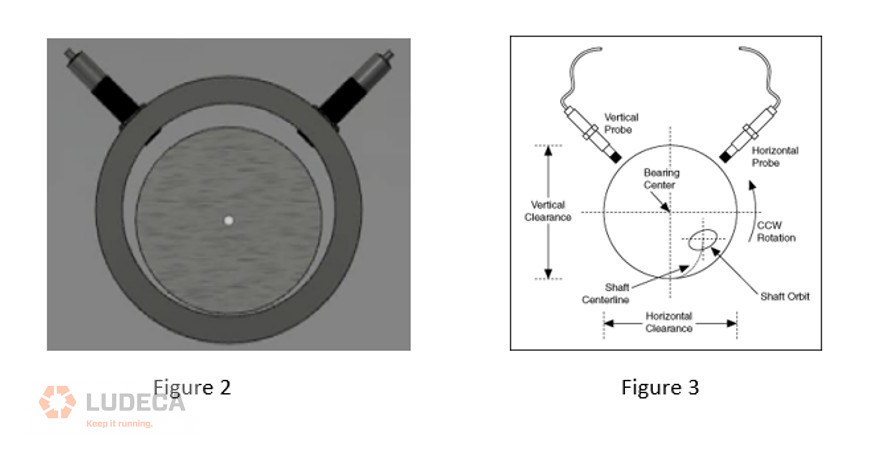

Proximity Probes

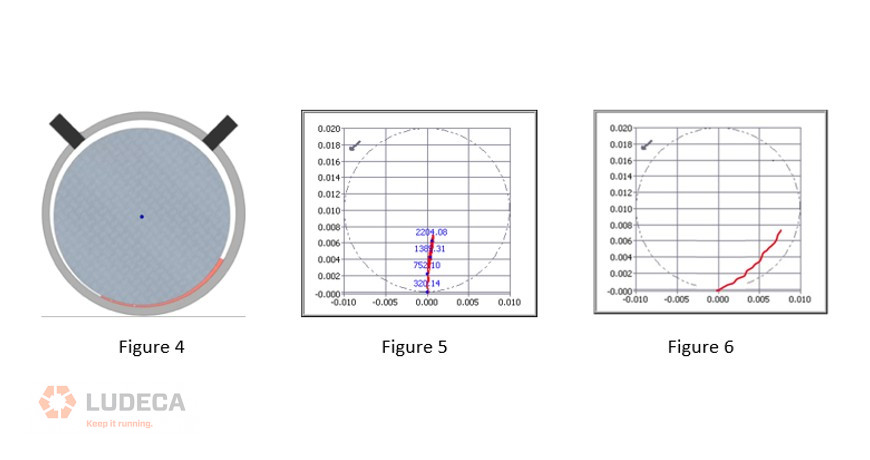

One typically uses two proximity probes, also called eddy current probes, when monitoring a journal bearing. The probes are permanently installed and mounted 90 degrees from each other (Figure 2). This gives us a two-dimensional view of the shaft’s position in the bearing. The AC voltage from these probes is used to measure shaft vibration and is often displayed in a 2D plot called an orbit. Figure 3 shows the relationship between the shaft centerline and the orbit. You can think of the centerline as the point the shaft is orbiting about.

As a shaft is run up in speed, the rotating shaft forces the oil to form a wedge in the bearing (Figure 4). The rotor will then sit on this oil wedge as it rotates around. Figure 5 is the shaft centerline diagram. The blue numbers on the plot are shaft RPM. The red line shows how the center point of the shaft has moved as the machine is sped up to running speed. In this case, up and a little to the right, which is normal for a tilt pad bearing rotating counterclockwise. Figure 6 shows an abnormal centerline plot where the rotor is too far to the right edge of the bearing. This could be the result of misalignment.

The shaft centerline plot is essential for journal bearing monitoring. Abnormal rotor positions can indicate all sorts of problems. This plot should be routinely measured and analyzed when monitoring journal bearings.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Alan Friedman dba Zenco offers machinery vibration analysis courses and certification in accordance with ISO 18436-2. Click here to check out his course schedule, you can also connect with him on Linkedin. In addition to public classroom training and public virtual courses, Alan is also available for private courses virtually or on-site in addition to informal training and mentoring. Category I and II vibration are also available in Spanish.

Alan, aka the Vibe Guru, has over 30 years of vibration analysis experience, He has trained thousands of students around the world up to Category IV. One of the things that makes Alan a great teacher is his ability to teach people where they are at. Whether you are a math-challenged millwright, an engineer, or a PhD, Alan will challenge you without overwhelming you. If you are interested in condition monitoring you can also check out his book: Audit It. Improve It! Getting the Most from your Vibration Monitoring Program or hire him for an on-site program audit.

by Diana Pereda

As wireless sensors are starting to become mainstream in the condition monitoring world, there are now many more choices to consider when selecting a system to fit your needs. This tip aims to look at the key features that will impact your decision. When purchasing your next wireless system, quiz your supplier using the information below.

Data Captured

Not all wireless sensors are created equal. Some will only capture an OA, or Overall Value, which is a single number indicative of the amount of vibration measured at the sensor. OA is useful for detecting certain types of faults, but it will not assist in diagnosing the problem, or inform the user of how severe the potential issue is. The good news is that there are a lot of sensors on the market that capture a full time waveform, TWF. This waveform can be transformed into a spectrum revealing the energy associated with the underlying frequencies. Using both a TWF and Spectrum is a reliable tool for diagnosing faults.

One step better is a sensor that will capture both an OA value regularly, and a TWF periodically – ensuring both a timely and informative strategy.

Fmax

This is the maximum frequency your sensor will capture, higher values allow for detecting faults on higher speed machines, or on very low speed machines (providing the sample window is sufficient). The general rule of thumb is Fmax = 70 x Running Speed. As the vast majority of wireless sensors are tri-axial, you should ensure you are aware of the Fmax for each axis, as you may only need a high Fmax reading in one axis.

Installation and Maintenance

Ease of installation is a huge area for wireless sensors. Does the sensor and gateway come pre-linked? How do you connect a new sensor to a gateway? Can you easily swap a sensor should one need replaced? Ask your supplier to show you a typical installation so you understand the time involved.

Wireless Technology & Range

There are numerous wireless technologies available, but make sure you are aware of the pros and cons of each before choosing your supplier. WiFi and Bluetooth (both 2.4GHz) are very common and easy for most to understand, but their range can be limited when used in an industrial environment, furthermore, some factories control their entire plant using 2.4GHz and will simply not allow the addition of more transmitters on that frequency.

Other technologies such as LoRa and ISM will utilize sub-1GHz bands and will not interfere with existing equipment. They also benefit from better propagation through certain materials due to their lower frequency, meaning better range for similar battery life – with less existing equipment on this band, it will trouble IT teams much less.

Battery

There’s no point having a wireless sensor if it’s powered via cables – thus most, if not all, wireless sensors are battery powered. You will find two key options, non-replaceable and replaceable.

Non-replaceable batteries will benefit when it comes to ingress protection and intrinsic safety. As the sensor will not be user serviceable, it greatly increases robustness. Replaceable batteries increase the useable life of the sensor – but be aware of misleading claims from manufacturers quoted battery life, as it can typically only be achieved when the sensor is in a low power state and limited use mode – ask your sensor supplier for the true battery life for your given application. The more times you have to replace a battery, the greater cost to you, mostly for the time it takes to replace (on average $100 per sensor), so higher battery life is better, even for replaceable battery.

Thank you, David Proctor, with Sensoteq for sharing this educational blog with us!

by Diana Pereda

In Are Harmonics Real? Part 3, I offered some examples of resonance where the natural frequencies of a system are also harmonics. This is not the norm for most objects, but it is was worth mentioning to avoid confusion.

What Does LinkedIn Think?

I asked the LinkedIn community what they think about this question, both before and after writing my articles. It seems I did not do a very good job of changing minds! The poll below still had 5 days to run, the sentiment is clear. That said, this is in no way a scientific poll. I did not ask the same people for their opinions before and after reading the articles. Many thousands read the articles and only 114 answered the poll. I also have no way of knowing if the people who responded to the poll actually read any of the articles.

I argued for many years that harmonics are NOT real, so I certainly can see why intelligent people might still think that (even though I proposed some simple experiments in these articles to prove that they are in fact real!)

What Do Our AI Overlords Have to Say About It?

They say the AIs are going to replace us, so I thought I would survey a few LLMs to see what they had to say on the subject.

Question 1: A clipped wave will produce harmonics in the FFT. Are the harmonics “real” or are they just a product of the FFT algorithm?

CoPilot

The harmonics observed in the FFT of a clipped wave are indeed “real” in a mathematical and physical sense. When a wave is clipped, the process introduces sharp transitions or discontinuities, effectively altering the waveform. These abrupt changes result in the addition of high-frequency components that were not present in the original signal. The Fourier Transform (FFT) mathematically represents the wave as a sum of sinusoids, so it picks up on these newly introduced frequency components—these are the harmonics you see.

In other words, the harmonics are not artifacts of the FFT algorithm itself; they are genuinely present due to the clipping process. The FFT just reveals them. Clipping is a type of non-linear distortion, and harmonics are a natural byproduct of such distortions in signal processing.

Gemini

The harmonics produced in the FFT of a clipped wave are real, not just a product of the FFT algorithm. Here’s why:

- Clipping introduces non-linear distortion: When a waveform is clipped, its shape is fundamentally altered. This abrupt change in the time domain signal introduces new frequency components that were not present in the original, unclipped signal.

- Harmonics are inherent to non-sinusoidal periodic waveforms: Any periodic waveform that isn’t a pure sine wave is composed of a fundamental frequency and its harmonics (integer multiples of the fundamental frequency). Clipping a sine wave forces it to become a non-sinusoidal, albeit distorted, periodic waveform.

- The FFT reveals existing frequency content: The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is a mathematical tool that analyzes a time-domain signal and decomposes it into its constituent frequencies. It doesn’t invent frequencies; instead, it reveals the frequencies that are already present in the signal.

- Experimental verification: You can observe these harmonics using a spectrum analyzer (which essentially performs an FFT in hardware). The presence of harmonics after clipping is a physically measurable phenomenon, not an artifact of the FFT process itself.

- Think of it this way: Clipping adds energy to the signal at specific harmonic frequencies due to the waveform distortion. The FFT accurately identifies and quantifies these newly generated frequency components. While the FFT algorithm itself has certain characteristics and potential artifacts (like spectral leakage or aliasing if not used correctly), the harmonics seen in the FFT of a clipped wave are a genuine representation of the altered frequency content of the signal caused by the clipping process.

DeepSeek

When a waveform is clipped (either hard or soft clipping), the resulting distortion introduces real harmonics into the signal. These harmonics are not just artifacts of the FFT algorithm but are physically present in the time-domain signal due to the nonlinear distortion caused by clipping.

Why Are the Harmonics Real?

- Mathematical Basis (Fourier Series/Transform)

- Nonlinear Distortion Mechanism

- FFT as a Measurement Tool

Practical Confirmation

- If you observe a clipped sine wave on an oscilloscope, you can clearly see the flattening (hard clipping) or smoothing (soft clipping).

- A spectrum analyzer (which doesn’t use an FFT) would still show the harmonics.

- Analog systems (e.g., guitar distortion pedals) produce these harmonics without any digital processing.

Conclusion

The harmonics produced by clipping are real and not an artifact of the FFT. The FFT merely reveals them as part of the signal’s true frequency content.

Question 2: As a follow-up to the last question. Let’s say the fundamental frequency of the clipped wave is 30 Hz. The clipped wave is measured on a vibrating table. If I attach a spring with a natural frequency of 60 Hz to the table, will it resonate?

CoPilot

Resonance occurs when the frequency of an external driving force matches the natural frequency of the system—in this case, the spring’s natural frequency of 60 Hz. The fundamental frequency of the clipped wave is 30 Hz, which is half the spring’s natural frequency. However, the harmonics generated by the clipping process could include a frequency component at 60 Hz, depending on how the waveform is distorted.

If the 60 Hz harmonic is present in the vibration caused by the clipped wave, the spring could potentially resonate. This is because resonance doesn’t solely depend on the fundamental frequency—it can also be driven by harmonic components of the waveform that match the spring’s natural frequency.

To test this, you would need to analyze the FFT of the clipped wave to confirm the presence of a 60 Hz harmonic. If it exists and has enough energy to excite the spring, resonance is a plausible outcome.

Gemini

Yes, the spring with a natural frequency of 60 Hz will likely resonate, although the strength of the resonance will depend on several factors. Here’s the breakdown:

- Harmonics are present: As we discussed, clipping a 30 Hz wave introduces harmonics, which are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency. One of these harmonics will be at 60 Hz (the second harmonic).

- Resonance occurs at the natural frequency: Resonance is the phenomenon where a system (in this case, the spring) vibrates with maximum amplitude when driven by an external force at or near its natural frequency.

- The 60 Hz harmonic acts as a driving force: The vibrating table, driven by the clipped 30 Hz wave, will contain a significant component at 60 Hz due to the clipping. This 60 Hz component will act as a periodic driving force on the attached spring.

- Matching frequencies lead to energy transfer: When the driving frequency (the 60 Hz harmonic from the table) matches the natural frequency of the spring (60 Hz), energy will be efficiently transferred to the spring, causing it to oscillate with a larger amplitude – this is resonance.

In conclusion: Because clipping introduces a harmonic at 60 Hz, which matches the natural frequency of the spring, you can expect the spring to resonate.

DeepSeek

Yes, the spring with a natural frequency of 60 Hz will resonate if the clipped wave contains sufficient energy at that frequency (the 2nd harmonic). Here’s why:

- Harmonics in a Clipped Wave

- A clipped wave (hard or soft clipping) generates real harmonics at integer multiples of the fundamental frequency (30 Hz).

- The strongest harmonics are typically the odd-order (90 Hz, 150 Hz, etc.), but even-order harmonics (60 Hz, 120 Hz, etc.) are also present, especially in asymmetrical clipping.

- Resonance Condition

- Resonance occurs when a system’s natural frequency matches an excitation frequency.

- If the clipped wave has a 60 Hz component (2nd harmonic), and the spring has a natural frequency of 60 Hz, it will resonate if:

- Will the Spring Resonate?

- Yes, if: The clipping is severe enough to produce a measurable 60 Hz harmonic. The system has low damping (e.g., a lightly damped spring).

- No or weakly, if: The clipping is mild (weak harmonics). The system is heavily damped. The wave is symmetrically clipped (which suppresses even harmonics, leaving mostly odd ones like 90 Hz).

Practical Consideration

- If the clipped wave is symmetrical (e.g., centered around zero), the even harmonics (60 Hz, 120 Hz, etc.) will be weaker or absent, meaning resonance at 60 Hz may not occur.

- If the clipping is asymmetrical, even harmonics will be stronger, increasing the chance of resonance at 60 Hz.

- You could verify this by running an FFT on the vibrating table’s motion to see if 60 Hz is present.

Conclusion

Yes, the spring will likely resonate at 60 Hz if the clipped wave contains enough energy at that frequency. The presence of even harmonics depends on the clipping symmetry, but in many real-world cases, some 60 Hz content will exist, leading to resonance.

Conclusion

LinkedIn poll answering community Vs LLMs? I’m going to side with the LLMs on this one! I want to reiterate that I spent a number of years arguing that harmonics are NOT real before I changed my mind. I also want to note that I wrote the articles on this topic BEFORE I asked the LLMs to weigh in.

Still not convinced? Why not try the experiments I proposed in the article and see for yourself? If you have an 1800 RPM motor, put a spring on it that is tuned to 60 Hz (2x) and see if it vibrates. If the 2x harmonic is not real, the spring will not vibrate. Or, hit a bell with a mallet and see if it rings. If the hit does not contain the natural frequencies of the bell, the bell will not ring.

You might also query the LLMs yourself and look at the sources they cited to come to their conclusions.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Alan Friedman dba Zenco offers machinery vibration analysis courses and certification in accordance with ISO 18436-2. Click here to check out his course schedule, you can also connect with him on Linkedin. In addition to public classroom training and public virtual courses, Alan is also available for private courses virtually or on-site in addition to informal training and mentoring. Category I and II vibration are also available in Spanish.

Alan, aka the Vibe Guru, has over 30 years of vibration analysis experience, He has trained thousands of students around the world up to Category IV. One of the things that makes Alan a great teacher is his ability to teach people where they are at. Whether you are a math-challenged millwright, an engineer, or a PhD, Alan will challenge you without overwhelming you. If you are interested in condition monitoring you can also check out his book: Audit It. Improve It! Getting the Most from your Vibration Monitoring Program or hire him for an on-site program audit.

Case Study: Eliminating High Vibration Due to Natural Frequency

by Diana Pereda

How do you read this? Well, that depends on who you are and what your position is in your organization. If you are an area owner and this is one of your critical machines, then you’ll probably be really happy. Readings are being taken and everything looks good. The actual alert and alarm limits, enveloped spectrum alarms, high-frequency detection-that’s all been taken care of by the reliability department.

On the other hand, if you’re a technician and it’s your job to take these readings with a hand-held data collector, this trend can be described with one word – boring. While there is always value in taking a reading on a rotating asset and using your 5 senses to look for issues that might not be picked up with vibration, this only extends so far for machines that rarely have issues. For AHUs with sensors already mounted and cabled to the outside with BNC connections, you’re not even using the 5 senses. The most difficult part of the job is keeping your concentration and matching the asset in the route to the asset you are at. This has to compete with your attention span which might drift to what you’re going to have for dinner tonight or what you might watch on Netflix after. The technicians of today are hungry to learn and want to be as much a part of Industry 4.0 as anybody else. They will naturally gravitate to work that is interesting and challenges their grey matter. Taking readings on AHUs does not do this, especially if they are not involved in the analysis.

So, if you already have sensors on your AHUs, why not go the extra mile and stick a transmitter on the outside and send all that data up to the cloud. The reliability team are then not limited to one reading a month to figure out what’s actually going on. If you have your sensors on process equipment, then you can not only look at data related to machinery diagnostics, you can export your overall trend into a data analytics package and overlay vibration against pressure, tank levels, valve states, flow rates. Maybe your pump is dead-heading against a manual valve that has no feed-back. Maybe it’s pumping against a partially closed control valve that is choking flow so the system can come up to temperature. This would then result in increased axial vibration, possibly over the alarm limits, that would then prompt an analyst to recommend a pump check, focusing on the coupling. In reality, this will be a temporary rise in vibration and by the time the technician gets there, will probably be passed. Maybe it’s being fed from a tank and the low-level interlocks aren’t working so it’s cavitating. Take it one step further and you can look at flow-induced vibration from where the system curve intersects the flow curve for different flow rates. A whole new world opens up.

To do this, you’ll need to think of systems as opposed to just individual assets. P&IDs, dampers, control valves, tank levels, flow rates-all the information from this instrumentation will form part of your assessment as opposed to just drive end and non-drive end vibration. This scenario is coming to an organization near you, whether you like it or not. You just have to decide if you want to be a part of it.

Thank you Sensoteq for sharing this educational article with us!

by Diana Pereda

In Are Harmonics Real? Part 2, I suggested that a single hit or impulse can be thought of the same way. If a tuning fork has a natural frequency of 60 Hz, it will not make a sound unless it is excited at 60 Hz. It does however make a sound when you strike it against your hip. This means that the single strike or single impulse must contain “real” vibration at 60 Hz. Although I did not hit the tuning fork 60 times per second, the single impulse “contains” that frequency. It is not just a by product of the FFT.

Non Linearity

Why are there frequencies in the output that do not exist in the input? If I bounce the mass on the spring up and down at 30 Hz, why do I also get frequencies at 60, 90, 120 Hz Etc? The answer is non-linearity. In a non linear system you get things in the output that were not present in the input. You can read more about that in my article, Linear and Non-linear Vibrations.

An Example of Harmonics that are Real in a Different Way

There are a couple of interesting cases where harmonics are “real” in a different way. I’ll give you a hint: We like the sound of harmonics.

If you have a string connected at both ends, like a guitar string, the modes or natural frequencies are also harmonics. If for example the first mode or natural frequency is 30 Hz, the 2nd will be 60 Hz and the 3rd 90 Hz etc. The reason for this is that the modes break up the space into equal divisions create a pattern of “standing waves” whereby the vibration reinforces itself. If the wave shape doesn’t perfectly fit, the waves will be out of phase and will cancel out.

This is NOT true for most structures!!! In a bell, the first natural frequency might be 30 Hz, the 2nd might be 97.3 Hz and the 3rd might be 104.8 Hz. In other words, in most structures, the modes are NOT harmonics of each other.

Can you Think of Another Example?

Can you offer another example where the modes or natural frequencies are also harmonics? I gave you a hint that we like the sound of harmonics.

The other example is a tube filled with air – as in a pipe organ. In this case, the sound waves in the air bounce off then ends of the pipe. The wavelengths that perfectly fit in the space or that perfectly divide it up, will reinforce themselves. Those that don’t perfectly fit in the space will bounce back out of phase and will cancel each other out.

The fundamental frequency and harmonics generated by a pipe organ are therefore related to the length of the tube.

Keep your eyes open for another article in thus series where we’ll see what out AI overlords have to say about the reality of harmonics. In the meantime…

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Alan Friedman dba Zenco offers machinery vibration analysis courses and certification in accordance with ISO 18436-2. Click here to check out his course schedule, you can also connect with him on Linkedin. In addition to public classroom training and public virtual courses, Alan is also available for private courses virtually or on-site in addition to informal training and mentoring. Category I and II vibration are also available in Spanish.

Alan, aka the Vibe Guru, has over 30 years of vibration analysis experience, He has trained thousands of students around the world up to Category IV. One of the things that makes Alan a great teacher is his ability to teach people where they are at. Whether you are a math-challenged millwright, an engineer, or a PhD, Alan will challenge you without overwhelming you. If you are interested in condition monitoring you can also check out his book: Audit It. Improve It! Getting the Most from your Vibration Monitoring Program or hire him for an on-site program audit.

by Diana Pereda

In Are Harmonics Real? Part 1, I noted that a sine wave, perhaps created by a mass on a spring bouncing up and down, results in a single peak in the spectrum. If the spring gets more rigid as it gets compressed, the mass will move less in one direction than the other. We can describe the form of the wave this makes as distorted or clipped. When we pass this clipped wave through the FFT, we get harmonics or multiples of the fundamental frequency.

For example, if the mass bounced up and down 30 times per second, we would see a peak in the spectrum at 30 Hz. If it was clipped, we would also see peaks at 60, 90, 120 and 150 Hz etc. These are called harmonics. The question I posed is: Are the harmonics real? In other words, although the mass is still only bouncing up and down 30 times per second, is there actually real vibration occurring at 60, 90 and 120 Hz Etc? OR are these just artifacts of the FFT?

I posted this question to LinkedIn. Here are the responses:

Apparently, 65% of the respondents believe that harmonics are NOT real, but just a product of the FFT. Only 21% think harmonics are real. Perhaps popular opinion is not a good gauge of truth?

Natural Frequencies and Resonance

I am going to go off on a little tangent to talk about natural frequencies and resonance. In this tangent, I will propose an experiment that people can try themselves to prove if harmonics are real or not.

A single mass spring system has a single natural frequency. If you pull the mass down and let it go, it will vibrate at this frequency. A tuning fork is the same. It has one primary frequency it likes to vibrate at. A bell has numerous natural frequencies, but they also won’t ring if they are not excited by the same frequency.

A natural frequency is a property of the structure, related to its mass, stiffness and damping. Resonance is a condition where the natural frequency is excited by a forcing frequency. In the case of a tuning fork, it has a natural frequency, BUT if it is just sitting on a table, that natural frequency is not excited (it is not in resonance) and the tuning fork does not make a sound. If you shake it back and forth in your hand – Eg. vibrate it at a frequency other than its natural frequency, it also doesn’t make a sound. It only makes a sound when the natural frequency is excited.

This concept is very straight forward in vibration. I am not sure why the LinkedIn community got this wrong. If the natural frequency is NOT excited, the bell WILL NOT ring. On a positive note, I know where people can get some great vibration training! Y’all need it! 😉

A Single Impact

In Are Harmonics Real? Part 1, I noted that a single impact in time creates broadband noise in the spectrum. The FFT basically says: “Give me a wave and I’ll give you a bunch of sine waves. If you add these sine waves together, they will look like the original wave.” People who don’t think harmonics are “real” might say that they just come from the FFT trying to define the shape of the wave by adding sine waves together.

If you have a single impact in time, it looks nothing like a sine wave at all and the FFT spits out sine waves at lots of frequencies to try to define it. We call this broadband noise. People who believe that harmonics are not real will also believe the broadband noise is not real for the same reasons.

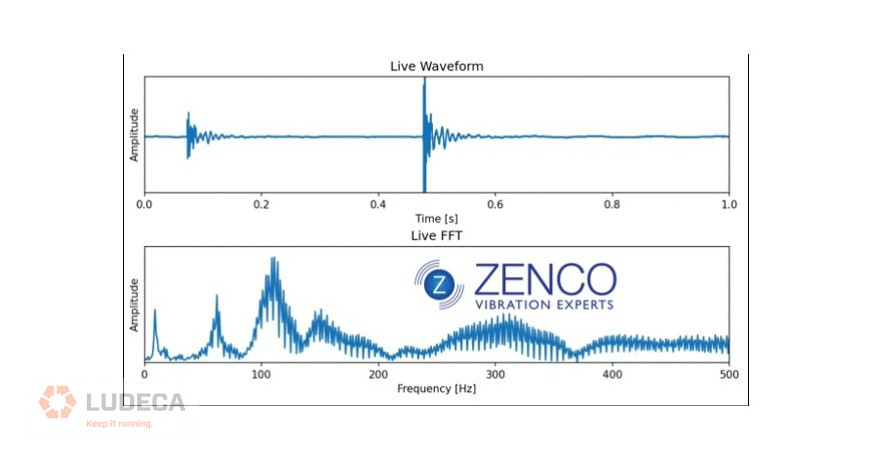

A single hit creates noise in the spectrum

Looking at the animation above. I am only tapping the structure once, but you see vibration all the way across the spectrum. There’s a hump just above 100 Hz, but I am not tapping anything 100 times per second. Therefore, this vibration must not be real. Right? I am also not tapping it 300 times per second and yet the spectrum shows vibration at that frequency (and all the frequencies between) as well.

I am asking the same question here. Is the broadband noise “real” or just an artifact of the FFT?

An Easy Experiment

I am using the example of broadband noise to make the case for harmonics being real because this one is more intuitive and easier to test. If you think harmonics are NOT real, you will also think broadband noise is NOT real for the same reasons. I am clearly only tapping the object once, not 100 times per second or 300 times per second or anywhere in between, so these frequencies must not be real… That’s how the thinking would go.

So, let’s say a bell or a tuning fork has a natural frequency of 1000 Hz. If you hit it once, does it ring at that frequency? Yes it does! That means that there really is vibration at 1000 Hz being input into the bell. That single tap does include real vibration at 1000 Hz. It is NOT just the FFT trying to come up with a bunch of sine waves that when added together will look like our input.

You could also prove that different “taps” include different frequencies, even if the tap itself only happens once. A drum head has a lot of natural frequencies – none of which will make a sound if it is not excited by the same frequency. If you hit a drum with a soft mallet, it makes a different sound than if you hit is with a wooden drum stick. Why is this? It is because the soft mallet only injects (or contains) lower frequencies and therefore only excites the lower modes or natural frequencies of the drum head. It makes a lower sound. A wooden drum stick injects lower and higher frequencies, so in addition to the low tones, you also get higher ones.

An Easy Experiment for Harmonics

With the last experiment in mind, we can prove the existence of harmonics in the same way. Let’s say we have the mass and spring bouncing up and down 30 times per second (30 Hz) but the wave is clipped due to the spring getting more rigid as it compresses. The FFT will contain 30 Hz and harmonics at 60, 90, 120 Hz etc.

To prove that the harmonics are “real,” we could attach another spring with a natural frequency of 60 Hz to the first spring. If the spring tuned to 60 Hz vibrates, it means there is in fact really vibration at 60 Hz, it is not an artifact or output of the FFT.

In the case of a machine, if it rotates at 1800 RPM (30 Hz) you could mount a spring on it with natural frequency of 60 Hz. If the spring vibrates, then there really is vibration occurring at this frequency.

Back in the old days (before my time) they had mechanical vibration sensors that were just a series of little masses on springs tuned to different frequencies. You placed it on a machine and looked to see which springs vibrated. This is how you knew which frequencies were present.

Non Linearity

Why are there frequencies in the output that do not exist in the input? If I bounce the mass on the spring up and down at 30 Hz, why do I also get frequencies at 60, 90, 120 Hz Etc? The answer is non-linearity. In a non linear system you get things in the output that were not present in the input. You can read more about that in my article below, Linear and Non-linear Vibrations.

Another Example of Harmonics that Real in a Different Way

In article 3, I’ll offer up a couple of cases where natural frequencies are also harmonics. Keep an eye out for it!

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Alan Friedman dba Zenco offers machinery vibration analysis courses and certification in accordance with ISO 18436-2. Click here to check out his course schedule, you can also connect with him on Linkedin. In addition to public classroom training and public virtual courses, Alan is also available for private courses virtually or on-site in addition to informal training and mentoring. Category I and II vibration are also available in Spanish.

Alan, aka the Vibe Guru, has over 30 years of vibration analysis experience, He has trained thousands of students around the world up to Category IV. One of the things that makes Alan a great teacher is his ability to teach people where they are at. Whether you are a math-challenged millwright, an engineer, or a PhD, Alan will challenge you without overwhelming you. If you are interested in condition monitoring you can also check out his book: Audit It. Improve It! Getting the Most from your Vibration Monitoring Program or hire him for an on-site program audit.

by Diana Pereda

Are harmonics real or just an artifact or result of processing the waveform through the FFT? This is a question that comes up a lot among vibration analysts, or anyone working with signals and signal processing.

What Are Harmonics?

A sine wave has a single amplitude and frequency. Let’s say our sine wave has a frequency of 25 Hz and a peak amplitude of 10. If you use the FFT algorithm to convert a sine wave to a spectrum, you will see a single peak at 25 Hz with a peak amplitude of 10. You can see this at the beginning of the animation above. At the starting point there is a sine wave at the top and the spectrum below with a single peak at 25 Hz.

A wave that repeats itself but is not a sine wave results in harmonics in the spectrum. You can also see this in the animation above. As I clip or flatten the top of the wave, you can see the harmonics appearing in the spectrum. Harmonics are multiples of the base frequency. In this case they are 25 Hz x 2, 25 x 3, 25 x 4 etc. giving us peaks at 25 Hz, 50 Hz, 75 Hz, 100 Hz etc.

The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)

The FFT is a tool that reveals the frequency components present in a signal. It breaks the signal down into a series of sine waves.

Another way of phrasing this is: The FFT essentially says “give me a wave and I will give you a bunch of sine waves. If you add all these sine waves together, it will look like the initial wave.” This is my layman’s way of understanding it anyway.

Each peak in the spectrum represents a sine wave. If I were to add the sine waves represented by the peaks at 25, 50, 75 and 100 Hz etc. at the end of the animation above, the resulting wave would look just like the clipped wave.

But Are Harmonics Real?

One view of this is that the wave I used for this explanation is not “real” in that it is something I generated in software. I also clipped it in software, so the peaks at 50, 75 and 100 Hz don’t correspond to anything real in the physical world, so they must just be artifacts or things stemming from running the data through the FFT. Right?

A Physical Representation of Clipping

Let’s say I move a mass and spring back and forth 30 times per second (30 Hz) with a sinusoidal force (a sine wave) but as the spring compresses, it gets more rigid and eventually stops compressing. This will create a clipped wave as in the image below. When I pull the mass out, it looks like a sine wave, when I push it in, compressing the spring, it gets flattened.

As we noted before, the clipped wave is repetitive but not a sine wave and therefore we will get harmonics. As you can see from the image above, we have peaks at 30, 60, 90 and 120 Hz.

One might look at this physical example of a clipped wave and they might say: “I see the mass moving back and forth 30 times / second. I do not see anything happening at 60 times per second or at 90 times per second, so harmonics can’t be real. They must just come out of the FFT algorithm.”

Repetitive Impacting

Another example of a wave that is repetitive but not a sine wave is repetitive impacts. If I take a drumstick and I hit a drum 5 times per second (as in the time waveform image below) I would see peaks in the spectrum at 5, 10, 15, 20 Hz etc. In other words, harmonics. Intuitively you know that you are only hitting the drum 5 times per second, so why would there be frequencies at 10, 15 and 20 Hz etc. in the spectrum? They must just come out of the FFT right?

The pattern above is common in machinery vibration analysis. This could be a bearing with a defect on the race and the impacts are the balls or rollers slamming into that defect one after the other. This could also a be a broken gear tooth that causes a big impact every time it comes into contact with the other gear. In both cases, the analyst would expect to see harmonics of the defect frequency in the spectrum.

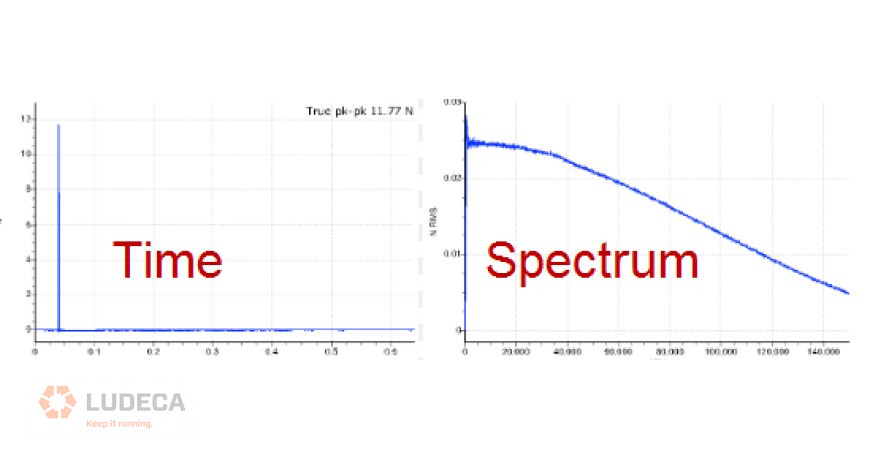

A Single Impulse or Impact?

A common test in vibration analysis is to strike an object with a calibrated hammer. The calibrated hammer has a force sensor in its tip, so it measures the actual hit. If we look at this in the time waveform, we see a single sharp, short duration pulse. When we convert this pulse to a spectrum, we get vibration at many frequencies or what is referred to as “broadband” noise.

One might say: “The FFT has a really hard time describing that single impact by adding sine waves together. The only way to do it is to add sine waves together at every frequency as shown in the image above.” These frequencies don’t exist in the real world though. (Or do they?)

I will ask again, using this example, are the frequencies shown in the spectrum for this single impact “real?” Do they really exist? Or are they just a result of passing that data through the FFT and the FFT trying to describe it by adding sine waves together?

Conclusion to Part 1

I want to leave this as an open question for now. Take some time, think about it, and decide for yourself if you think harmonics (and broadband noise) are real or not. In upcoming articles, I will lay out a case for what I think. I will also admit that my thinking about this has changed over the years. I used to take one side of this issue, now I lean towards the other. But you can decide for yourself.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Alan Friedman dba Zenco offers machinery vibration analysis courses and certification in accordance with ISO 18436-2. Click here to check out his course schedule, you can also connect with him on Linkedin. In addition to public classroom training and public virtual courses, Alan is also available for private courses virtually or on-site in addition to informal training and mentoring. Category I and II vibration are also available in Spanish.

Alan, aka the Vibe Guru, has over 30 years of vibration analysis experience, He has trained thousands of students around the world up to Category IV. One of the things that makes Alan a great teacher is his ability to teach people where they are at. Whether you are a math-challenged millwright, an engineer, or a PhD, Alan will challenge you without overwhelming you. If you are interested in condition monitoring you can also check out his book: Audit It. Improve It! Getting the Most from your Vibration Monitoring Program or hire him for an on-site program audit.

by Diana Pereda

Recently, while visiting a customer’s facility to provide onsite training for the vibration analysis tool they had purchased, we spent time building the database hierarchy (areas, machines and trending templates) before we started collecting data. The first room we entered had two large belt-driven overhung fans and even without collecting any data it was obvious that one of the fans was running extremely rough. After collecting data off both of the fans we stopped to review the data. As some of you with experience might already have guessed, the fan that was vibrating excessively had an extremely high turning speed (1×) amplitude.

Immediately the comment was made by the technician that his diagnosis was that the fan needed to be balanced, and if you simply looked at the vibration data that was the correct diagnosis; however, if you looked around the room and at the fans themselves, they were screaming clues about the root cause of the unbalance.

This facility was involved in the manufacture and processing of wood products which results in large amounts of wood dust being produced. These fans were designed to ventilate a high dust area and everything inside the room was covered in wood dust. It only makes sense that if everything inside the room was covered in wood dust, how much had also accumulated on the inside of the fan?

Before we walked back to the maintenance shop and informed the maintenance manager that we had a fan that needed balancing, I asked the technician if the fan could be stopped for a short period so that the inspection door could be opened. Once the fan was stopped and properly locked out, we opened the inspection door and found the fan blades heaped with accumulated stuck-on wood particles. After we had cleaned the fan blades, we had pile of wood chips which probably weighed somewhere around 5 lbs. We closed the inspection door and removed the lockout and asked operations to start the fan. Once the fan had been operating for a few minutes, we recollected data and the 1× fan amplitude had dropped significantly to a level that the fan no longer required balancing.

While it’s true that sometimes fans require balancing, often the cause is much simpler. Foreign material can build up on the fan blades and then suddenly a large piece comes off one of the blades causing the imbalance. This situation is more common than you might think, so before conducting any balance job perform a close inspection.

Watch our Balancing Know-How: Diagnosing Unbalance video for a quick introduction to diagnosing machinery unbalance with vibration analysis!

by Diana Pereda

There is a very simple, but crucial step in the machine installation process that oftentimes gets missed. When this step is missed, it leads to a world of problems, from excessive vibration to premature failure of bearings, seals, and especially couplings.

Let me establish the problem first, then I will explain how it negatively impacts the machine.

The problem

If some types of couplings are tightened before alignment, they ultimately end up in a bind. This bound condition can also be referred to as a “preloaded” condition. When this happens, an undesirable axial and radial load is introduced into the machines even though the shafts are aligned within tolerances.

Be aware of this potential problem and remember that some couplings should not be tightened until the shaft alignment is completed.

What types of couplings are susceptible to this issue?

This issue only affects coupling that have elements that bolt the two hubs together. These couplings typically have pieces that bolt to the outer or radial face of each hub. Although there are certainly others, the main types of couplings that are extremely susceptible to this are Omegas, Raptors (New Omega), and Rubber Tire couplings.

Some couplings are less or not affected by this problem, depending on how bad the initial misalignment is when the couplings are tightened. These might include gear couplings, grid couplings, and insert-type couplings. Shim pack type couplings are flexible couplings that are particularly rigid and can be affected by preload. Leave the final torque for the end!

Summary

Omega, Raptor, Rubber Tire, and other types of couplings that bolt up, easily bind up if you move the machine after they are tightened.

Gears, grids and inserts move more freely when they are aligned. One main reason for this is that these couplings have the ability for the connecting component to freely move axially.

What does coupling preload look like?

Let’s say you are a technician that is called out to troubleshoot a major vibration issue on a brand-new fan that you did not install. Let’s also assume that the millwright that did the install, tightened an Omega coupling and then aligned the motor to the fan.

If vibration data is collected it is likely to indicate misalignment with elevated 1×, 2×, and sometimes 3× in the spectrum. When the time waveform is analyzed, it will likely indicate binding that looks like misalignment.

Sometimes this preload condition can produce only an elevated 1× which would seem to indicate unbalance. The problem with preloaded coupling issues is that a laser alignment may look completely fine, and a balance will be unsuccessful and unnecessary. The only solution is to remove the preload condition of the coupling.

How to remove coupling Preload

Here’s the easy part. This problem is extremely easy to correct and even easier to avoid. To correct, simply loosen the coupling and retighten. This should relieve the preloaded condition. It is always a good idea to collect vibration data before and after, to document the improvement.

To avoid the issue, when dealing with preload-prone couplings, bolt the pieces of the coupling together but leave them loose. We need the hubs to rotate together in most cases for laser alignment. Align the shafts to tolerances, then tighten the coupling. When this happens in the proper sequence, everything is happy.

Conclusion

Be aware of the potential for coupling preload to affect vibration readings and machine health and strive to avoid this conditions from occurring in the first place, using the guidelines described above.

Download our Misalignment & Vibration infographic a reference guide to misalignment condition.

by Diana Pereda

There are different ways to understand machinery vibration analysis that people often confuse. Is vibration the cause of the problem, the result of the problem, or both? If you confuse these, you might make some big mistakes when analyzing data! So, let’s clarify…

Vibration as the Cause

When things vibrate a lot or “too much,” it can cause a lot of problems. Excessive vibration causes fatigue failures. Shafts, couplings, bearings, seals, pipes, foundations, and any structure, can actually be damaged by excessive vibration.

Excessive vibration can also cause quality problems in our products. Imagine an HVAC fan vibrating next to a computer chip printing machine. The vibration can travel through the floor from the fan to the machine and screw up our chips. Vibration can harm humans as well and even when it doesn’t harm us, it can annoy us – just think of that unbalanced ceiling fan going “whop whop whop” while you are trying to sleep.

A metaphor I like to use is: Imagine you are driving your car really fast on a really bumpy road. If you keep driving like that, the vibration will damage your car.

When I audit people’s vibration programs and I watch how they analyze data, I often see them thinking about vibration in this way. They look at a graph, look at the highest peaks, and say to themselves “This vibration isn’t too high, the machine is OK.” Or perhaps they use ISO RMS alarm charts and compare the measured vibration to the chart. Now I will explain why this is a big mistake!

Vibration as an Effect

When we use vibration in the context of #ConditionBasedMaintenance #CBM we are frequently looking at vibration as the effect rather than the cause, going back to the car metaphor. Imagine you drive your car to work the same way every day and one day you notice a new sound. You conclude “There must be something wrong with my car!”

In this case, we are not saying that the new sound is damaging the car but rather the new noise is an EFFECT or result of the damage. It is also possible that the amplitude of that new noise might be quite low, even if the damage is serious.

In a piece of rotating equipment, consider a defect on the outer race of a rolling element bearing. The balls or rollers hit the defect as they roll over it is creating a repetitive clicking. The amplitude of the vibration caused by a ball or roller hitting this little defect on the race through a layer of grease is pretty small compared to the vibration caused by water flowing through a pump or even by the shaft rotating around – BUT – the bearing is in fact damaged – AND – if we are just looking at our vibration to see if there’s anything “High” then we might miss this important fault. This is one reason why it is NOT ok to just look at vibration in terms of absolute amplitudes.

Effect and Cause

There are some cases where the vibration is both the effect and the cause. For example, if a rotor is out of balance, the vibration amplitude will increase at the shaft rate frequency (1x). This is an indicator that the rotor is out of balance. Why do we care that the rotor is out of balance? Because the increase in vibration resulting from the unbalance can cause damage to the machine. This therefore is a case where vibration is both effect and cause.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Alan Friedman dba Zenco offers machinery vibration analysis courses and certification in accordance with ISO 18436-2. Click here to check out his course schedule, you can also connect with him on Linkedin. In addition to public classroom training and public virtual courses, Alan is also available for private courses virtually or on-site in addition to informal training and mentoring. Category I and II vibration are also available in Spanish.

Alan, aka the Vibe Guru, has over 30 years of vibration analysis experience, He has trained thousands of students around the world up to Category IV. One of the things that makes Alan a great teacher is his ability to teach people where they are at. Whether you are a math-challenged millwright, an engineer, or a PhD, Alan will challenge you without overwhelming you. If you are interested in condition monitoring you can also check out his book: Audit It. Improve It! Getting the Most from your Vibration Monitoring Program or hire him for an on-site program audit.

Did you know that Alan Friedman left Mobius and is now providing his own courses?

by Diana Pereda

Visual inspections of equipment should always be completed during vibration data collection or the collection of any type of condition monitoring (CM) data. This important function is often overlooked and valuable information on the condition of your equipment is lost.

Looseness and many other conditions are commonly found as a result of a vibration analysis program. The source of these conditions should be corrected to improve the equipment’s reliability. Visual inspections can easily be completed on the machine while the data collector is acquiring the data. The visual inspection may reveal the source of these equipment issues. This will save time because future efforts will not be required to determine the cause of the issue.

Visual inspections may provide a confirmation to the analyst of the problem(s) uncovered by the vibration analysis program or other CM technology. It is important to diagnose and confirm problems to ensure accuracy in your CM efforts. Visual inspections may often provide the confirmation opportunity needed.

Safety issues are often uncovered by these routine visual inspections and can be corrected before an employee is injured. This could save a life and the resulting return on the investment is priceless!

by Trent Phillips

When purchasing vibration analysis equipment, consider the following seven factors to ensure you select the most suitable and effective solution for your specific needs:

- Expandability: Choose a vibration instrument that can be upgraded with additional features and measurement capabilities as your needs grow. This ensures that your investment remains valuable and relevant over time.

- Reporting Capabilities: Look for a vibration analyzer that can generate comprehensive reports containing diagnostic results, complete with photos and notes. Detailed reporting is essential for clear communication and thorough documentation of findings.

- Advanced Diagnostics: Opt for vibration analysis systems such as the VIBWORKS LT that incorporates the latest Artificial Intelligence (AI) diagnostics technology. These advanced systems can assist in identifying machine faults more efficiently, reducing downtime and maintenance costs.

- Training and Support: Ensure the availability of training, mentoring and support from the vendor. Adequate training ensures that users can fully utilize the system’s capabilities, while reliable technical support is crucial for addressing any issues that may arise in the field.

- Accuracy and Precision: Ensure the vibration analyzer provides high measurement accuracy and precision. Reliable and repeatable results are critical for effective monitoring and analysis of machinery.

- Ease of Use: Choose a vibration analysis tool that is user-friendly and easy to operate. Intuitive interfaces, built-in help features, and straightforward operation can significantly enhance user experience and efficiency, and reduce the training burden.

- Durability and Build Quality: Assess the durability and build quality of the vibration monitoring system. It should be designed to withstand the harsh conditions of industrial environments, ensuring longevity and consistent performance. A cost-efficient upgrade path is a plus.

By carefully considering these factors, you can make an informed decision when selecting a vibration data collector that meets your specific requirements. This approach will help you find a solution that not only addresses your current needs but also adapts to future demands.

by Diana Pereda

The days of measuring vibration data directly at the machine once every couple of months are starting to disappear. There is still huge value in undertaking this activity, but it’s quickly being replaced by a wide range of IIoT sensors (Industrial Internet of Things).

Seemingly, one advantage is gathering data at a vastly improved rate. Rather than a single reading every quarter, data can now be captured multiple times every hour. The advantages are obvious: much greater visibility on developing faults and a trail to follow to track existing known issues.

But there are also some disadvantages. IIoT devices are battery-powered, so there is a balance to be achieved in data quantity, quality, and battery life. Typically, the faster you acquire data, the lower the battery life. If not, then the quality of the data might suffer.

It’s All a Balancing Act

In the case of condition monitoring, this might be reducing the FMax, lowering the resolution or only sending the spectrum rather than the full-time waveform. This can sometimes be against the desires of Vibration Analysts, who want the cleanest, highest resolution appropriate for the application.

Another problem that exists with such large data sets; how do you quickly sift through all these data sets to find what you need to look at? Is too much data inhibiting you from viewing the pertinent data you need to analyze?

Get the Data You Deserve

If using these IIoT systems, make sure that you select one that provides a good interface to search through data sets. Data views that trend key features in the vibration information so that you can quickly detect anomalies and go straight to the corresponding data set. Focus on systems that provide a good frequent snapshot to understand a fast change in trends, but still measures high quality waveforms and spectrums suitable for analysis.

Accuracy is Still Key

One other factor to assess is the accuracy of the data you are analyzing. Ask yourself these questions; How accurate is the frequency? Is the FMax suitable for your application? Is the amplitude showing the true energy? Is the data fully processed and ready for me analyze?

There are many tools that aid in understanding your machine’s health. Choose one that works best for your needs, but never underestimate how important data quality is to achieving an accurate assessment.

Thank you Sensoteq for sharing this educational article with us!

by Diana Pereda

MYTH: “It is acceptable to use a stinger attached to the vibration sensor.”

TRUTH: Stingers can be attached and used with most vibration sensors. However, stingers are the least desirable method to mount the sensor to the equipment. Stingers reduce the frequency range that can be measured with the attached sensor. Also, it is very difficult to use the same amount of pressure to hold the sensor to the equipment each time. This may further reduce the signal response as well as the consistency and quality of data.

MYTH: “Applying generic overall amplitude values allows the correct trending and identification of equipment faults.”

TRUTH: An overall level is a single number representing the amplitude of a vibration measurement. Overall values can be derived in many different ways. You should be very cautious when assigning generic and/or the same alarm values to your equipment. Similar machines can operate at different vibration levels. The individual characteristics of each machine should be taken into consideration when setting valid alarm levels.

MYTH: “Collecting vibration data quarterly, semiannually, or annually on equipment will identify all equipment defects.”

TRUTH: The collection frequency of vibration data should be determined based on several factors. Some of these factors are equipment load, the operational speed of the equipment, operational frequency, criticality, and more. It is possible to calculate the optimal measurement frequency required to routinely identify equipment defects. Assigning some collection frequency based upon manpower or other means almost always results in equipment failures that were not detected in time or at all by the vibration program.

by Trent Phillips

Sensoteq Kappa X wireless sensors have been deployed at a petrochemical plant in the UK to monitor machine vibration and prevent facility downtime. By using the sensor system for continuous machine monitoring, concerning defects with a vacuum pump were detected. Vibration analysts identified several issues on Analytix and calculated a fixed cost saving of $84,627.27 since installation.

Machinery and Operations

The petrochemical plant processes chemicals derived from petroleum for widespread use across many industries, including fuel and manufacturing. These petrochemicals are used for fibers, solvents and thousands of other products. The site uses several vacuum pumps to remove all air and vapor particles from an enclosed space. If a pump fails, the reduced suction can increase pressure, causing fuses to overheat and burn out, leading to machine damage and costly failures.

Implementation

To monitor vibration issues and potential bearing fatigue and faults, Kappa X sensors were installed on pumps and compressors throughout the site to measure potential bearing fatigues or faults. By detecting early signs of bearing wear, misalignment, and other faults, the Kappa X sensors enable predictive maintenance, helping to prevent unexpected breakdowns and extend the lifespan of the machinery.

Thank you Sensoteq for sharing this educational article with us. Click here to continue reading!

by Diana Pereda

Tired of being a vibration analyst? Sick of getting raises? Want to move to a different place of employment or collect unemployment benefits? Here’s one of the most sure-fire ways to accomplish it: Make sure nobody in management at your current employer understands how valuable your services are.

Seriously now, it is essential to your job security that management understands the value and cost savings that you bring to the organization.

- Make sure you quantify the “avoided cost” realized by your company due to your efforts or the efforts of those who may report directly to you. But never exaggerate the numbers so that no one will take them seriously. Be honest with your savings calculations. A job well done will save so much that exaggerating it is never necessary.

- Make careful reports that communicate to management the return on investment of your hiring, deployment, or training. Do not hesitate to report work and results that make your managers look good to their managers. This will ensure your longevity and prosperity quicker than you can imagine. Managers always like looking good to their bosses.

Be diligent and honest in your work and the savings and benefits will follow of their own accord!

by Diana Pereda

Every analyst has a few things they really don’t want to hear during the course of their work. These comments often indicate that proper maintenance activities have not been performed on the equipment, or convey unrealistic expectations of the analyst’s abilities. For instance:

- “It has always run like that!”

- “It really was making a noise before you arrived.”

- “We don’t have time to change the bearings. Just balance the machine so we can run it.”

- “How long will it last?”

- “Those bearings are brand new so I know they’re good.”

- “Yeah, we just use a torch to heat bearings to install them.” Use a SURETHERM induction heater with automatic demagnetizing to properly install your bearings.

- “We don’t have a bearing heater so we use a pipe and hammer to drive the bearing on.” Use a SURETHERM induction heater with automatic demagnetizing to properly install your bearings.

- “All we collect are overall vibration values, they tell us everything we need to know.”

- “It doesn’t take us long to change belts cause we just roll them on.” Very bad practice! Use a laser tool like the SHEAVEMASTER and loosen the feet of the motor before installing the new belts.

- “We don’t use no fancy alignment tool. All we need is a straight edge.” A recipe for disaster! Get a good laser shaft alignment system like the Easy-Laser XT770 —the money this will save in lost production and unnecessary repairs will more than pay for itself, not to mention the time saved for the analyst who can now dedicate himself to finding other more complex vibration problems.

- “My screwdriver does not confirm your analysis!”

- “You found the problem. Now go fix it.”

- “I didn’t realize you needed training.” Sign-up for a LUDECA vibration analysis training class.

- “I didn’t realize that this CM technology would create so much work.”

- “We need you to stop using that CM technology and turn wrenches this week.”

- “We didn’t realize you had identified and created a work order to fix that problem before it failed.”

No doubt you’ve heard a few more! Feel free to share them with us.

by Gary James CRL

A vibration analyst is constantly viewing data and seeking to identify indications of sub-optimal physical properties indicated by specific vibratory behavior. Most complex systems (if vibration analysis is allowed to be called a system) can be broken down into simpler sub-systems. Some of us, this blogger included, benefit greatly from such simplification in the vibration analysis process. This blog is about one such simplification which may be a helpful addition to the reader’s set of vibratory behavioral pattern recognitions.

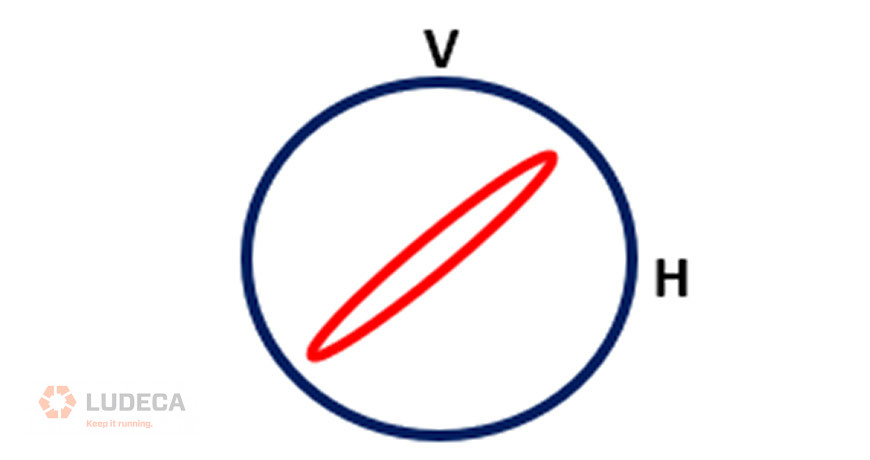

As an analyst progresses in the field of vibration analysis, they will come to appreciate the phase property of vibratory behavior. Phase is used most often to look for defects by comparing it across couplings, from top to bottom, or end to end of structures, machines, or machine trains, etc. Here, the author would like to offer a more simplified way to use phase than is often taught or talked about, at least by those who work mostly with anti-friction bearing machines.

Phase in a single bearing:

Let’s approach phase in its simplest form: a single shaft in a single rolling element bearing. A perfect shaft in a perfect bearing, with everything done perfectly; no unbalance, no misalignment, no defects, will have zero relative phase difference between V(ertical) and H(orizontal). In fact, it will not vibrate at all. Because perfection does not exist, we don’t need to worry about running into it.

The machines you will run into will vibrate and the vibration will have phase. The phase of vibration measured at a single bearing will be caused by the imperfections acting on that bearing/shaft assembly. Consider the most common “near perfection” you will likely encounter in the day-to-day life of a condition monitoring technician. This near perfection machine has been aligned well enough for misalignment to contribute virtually nothing to the vibration signal, no bearing defect vibration, only the slightest rotational frequency vibration presumably contributed by a miniscule amount of residual unbalance.

The phase at rotational frequency on this machine will have an almost perfectly circular orbit and show an almost perfectly predictable 90° relationship between H and V. Now consider, if the unbalance increases, without any contribution from other defects, this 90° phase relationship will become even more stark, because the amplitude will increase making the phase reading more stable.

What about misalignment?

If misalignment were introduced into our “near perfect” machine, the orbit of the shaft in the bearing would almost certainly lose its circular motion and take on a herky-jerky motion characteristic, because now the shaft is prevented from the motion that unbalance induces on the shaft, by the restraint imposed by the misaligned bearings. The fact is that the perpendicular phase will now tend toward being either 0° or 180°. Just like the 90°-phase relationship which gets more pure as unbalance severity increases, the 0° or 180° phase relationship is likely to become more pure with an increase in misalignment severity.

How can the phase relationship at two perpendicular bearing points on rotating equipment be 0?

One might wonder how the phase difference could be zero at two perpendicular points. In this case, it helps to visualize the orbit of the misalignment-restricted shaft within the bearing. In the bearing orbit shown in figure 1, the amplitude at rotational frequency recorded on the V sensor and that of the H sensor are maximum at virtually the same instant.

Cautions:

There are other less common possible causes of the vibratory behavior of the very elongated orbit, such as resonance. A simple way to rule out resonance when possible, is to change the rotational frequency by 15% and then make a new observation. A cocked bearing would be an even more unlikely suspect if shaft misalignment is ruled out.

Download our 4 Stages Bearing Failures infographic for a basic reference guide to understanding the stages of bearing failures.

by Diana Pereda