Bearings vs. Lubricants_ Regreasing

Commenting to Ana Maria Delgado CRL with LUDECA, about the bearings and the lubricants that keep them operating, it occurs to me to write about a point of view that few people observe.

We know bearings need grease; both to perform well and to last a lifetime. But do we really understand where that grease goes and how it performs its function?

There are two states that grease lives in when a bearing is lubricated. We refer to them as the Bleeding Phase and the Churning Phase. Let’s review so we can better visualize what’s happening in each phase.

Remember that grease is made up of oil, thickener, and additives. The thickener is the vehicle that delivers base oil to the war zone, where the rolling elements meet the races. These contact points are kept separated by the oil film that lubricates the contact point interface.

Let’s concentrate first on the churning phase. When there is thickener in the raceway, higher friction levels are present. The rolling elements must “plough” their way through this media. The result is higher temperatures from the bearing, and ultimately the motor. The motor consumes more electricity and the excess heat accelerates lubricant deterioration and consumption of additives.

When we over grease a bearing we cram thickener into the war zone; and we force that thickener to stay in the war zone. And that is a huge problem. It’s stuck there. That means the thickener sits there and gets run over by the rolling elements millions of times a day.

By crushing the thickener in the churning phase we’ve completely altered the properties of the lubricant and dramatically reduced its lifespan.

It is quite normal for the bearing and grease to be in the churning phase for a few seconds. This happens during grease replenishment, with each injection of new grease. The time for new grease to enter the bearing and settle to the grease cavity is called a stabilization period. Depending on the RPM of the bearing, this can be a few seconds or several minutes.

What lube techs must know is that their job is to transition the bearing from the churning phase to the bleeding phase as quickly as possible. This happens when a planned strategy for re-lubrication is in place, and they don’t exceed the calculated grease replenishment quantity.

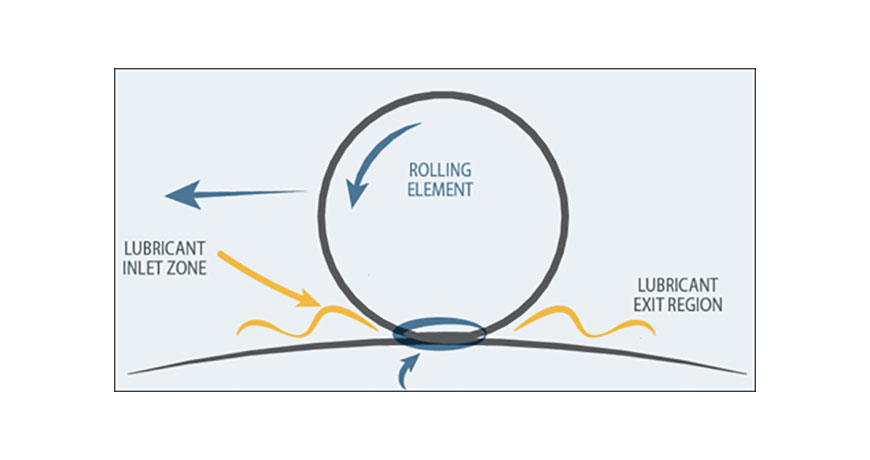

The bleeding phase describes the optimum condition where the right amount of grease resides outside the war zone, and the movement of the bearing allows only the base oil, infused with additives, to sufficiently bleed from the thickener to the space between the rolling elements.

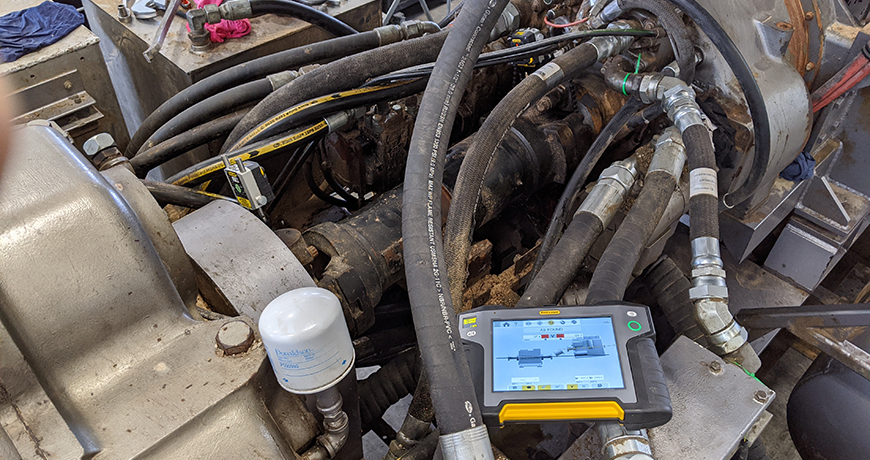

The only way to confidently know the bearing has reached an optimal churning phase is to measure its friction levels with an ultrasound instrument accurate enough to deliver repeatable, reliable data.

We welcome you to read the previous blog in this series, “What is Grease?”

Check out our LUBExpert, the ultrasound solution to avoid grease-related bearing failure! Plus, download our 5-Step Acoustic Lubrication Procedure an effective lubrication procedure to grease bearings right.

by Diana Pereda

Throughout our industry, technicians and maintenance personnel have been guided by various myths on how to lubricate their rolling elements. Some do take their time and try their best to calculate the correct amount, but in this day and age where we all have to do more with less, there is a drop in the quality of data provided to these important craftsmen.

After visiting various facilities across the country, you hear different answers in regard to the proper greasing of bearings. One that caught my attention was someone who asked me about the one-shot bandit. I had heard many terms in the industry but not that one. As I inquired, I figured it was the lubrication technician who pumps one shot, once a month. And there are the infamous three shots every three months time table provided to technicians. But nothing beats the one-shot, once-a-week for all bearings in a food processing facility I recently visited.

Let’s take a step back and take ownership of our craft. If we want to do more with less, we need to maximize the L10 bearing life. In order to do so, we need to ask the following questions before applying grease to any greasable bearing. They are:

Once we can answer these questions thoroughly and precisely, we should outfit our lubrication technicians with the appropriate tools to do their job, which is to grease bearings right! Hand them an ultrasound tool that will allow them to do precision acoustic lubrication. Let’s all become LUBExperts!!

Stop being a one-shot bandit and download our 5-Step Acoustic Lubrication Procedure to provide you with an effective lubrication procedure to grease bearings right!

by Diana Pereda

There are a lot of numbers and stats associated with lubrication; or, with the lack of proper lubrication in this case. For instance, it is said that 60% – 80% of bearing failures are related to lubrication issues of some kind; lack of lubrication, over- or under-lubrication, mixing lubricants that are incompatible, choosing the wrong lubricant for the application (such as the wrong grease or wrong viscosity oil), and finally, simply using a lubricant that is contaminated from the start.

The key to proper precision lubrication starts with the right mindset. We must believe that the lubricant is an “asset” and not just an ugly necessity. If we turn our mind towards precision lubrication with the precise “asset” for the application then our success rate for uptime will skyrocket. Think of trying to use a Philips head screw driver on a slotted screw. Simply put, it is the wrong tool for the application.

If we use a lubricant that is contaminated from the start, what chance are we giving the asset for success? What can we do to make sure the lubricants used are in the best condition for optimum performance? Let’s start at the beginning when the oil or grease first arrives at the receiving dock.

1. If we are receiving an oil, take a sample of the oil to make sure it is the oil that was ordered (proper type: hydraulic, gear, turbine, etc.), and is of the proper viscosity. Then check the cleanliness (particle count/ISO Cleanliness code) in which it was received from the supplier. Set it aside and wait for the results of the analysis before using.

2. Once we get the results back and are satisfied we received what was ordered, we should filter the oil with a kidney loop filtration system of some type because we know that new oil is not clean oil: especially hydraulic standard clean. Filter the new oil before using.

3. Take extra precautionary steps when filling the asset with the now clean oil so as not to contaminate the system with debris that has surely gathered on the asset. Best practice would be to have a completely closed system which filling with oil would require quick-connect adapters so the new oil can be transferred without ever having to open the system by fill port or by removing a lid. If this is not an option, make sure the transfer containers are color coded and sealed; do not use an open container or an open galvanized container. Be very careful not to inadvertently allow debris into the system.

4. The asset itself can be adapted for better success by implementing a desiccant breather, closing fill ports with quick-connects for filling and external filtration and perhaps a bottom water and sediment bowl for water and debris detection and removal.

5. The asset should have a label that matches the label on the oil container in the store room, the oil transfer cart and/or the color coded transfer container.

6. Implement an oil analysis program and keep an eye on the oil and asset health. If the sample comes back with good viscosity and additive levels but is dirty then filter it with the kidney loop system and get the oil back to the desired cleanliness level. Investigate where the particulate is coming from and take steps to prevent future particulate intrusion.

In conclusion, while there are many more steps we can take to maintain a healthy oil and therefore a healthy asset, these are some obvious action items we can implement for better success. Imagine if we turned the negative numbers of 60% – 80% into positive numbers for the company. Clean, healthy oil is an asset for success.

Download our Oil & Grease Storage Best Practices for additional tips to help outline the best practices for proper lubrication storage.

by Diana Pereda

Tremendous science goes into engineering the many grease formulations that keep physical assets working their best. The sheer number of grease types available is as varied as the applications where they are used. Yet their composition remains a simple mixture of base oil, thickener, and in most cases some additives.

The Base Oil is the key ingredient of grease. Its job is to form the thin, hydrodynamic film that separates metal components from one another. When functional separation between elements is maintained, the bearing has what we term a functional grease mechanism.

Base oil is the key ingredient when matching grease types to specific applications.

Thickeners are the matrix of the grease. Base oil cannot resist gravity on its own. It relies on the thickener to hold it in place. The thickener makes grease effective regardless of a machine’s orientation. For instance, in a vertically oriented shaft, the base oil would seep away from the bearing making a sustainable, functional grease mechanism improbably. In addition to keeping base oil where it’s needed, thickener has the added benefit of shielding the base oil from particle contaminants.

Additives are a double-edged sword.

On the positive side, they enhance the lubricating properties of the base oil. Additives increase the lubricity of the base oil making grease even more slippery. They help fight oxidation, corrosion, and extreme pressure conditions.

For additional information, download our Oil & Grease Storage Best Practices which includes helpful tips to outline the best practices for proper lubrication storage.

On the negative side, they are a consumable. They deteriorate over time, so their effectiveness is not linear for the life of the grease. Additives can also have adverse effects on the thickener.

Additives add an unknown function to the mad science of calculating time-based grease replenishment intervals. Most departments working on calendar-based lubrication don’t factor additives into the equation, further compounding their errors.

While considerable science goes into formulating grease types, what the lube technician needs to know is that the grease he or she injects into the bearing actually reaches its intended destination and works to form an effective greasing mechanism.

We welcome you to read the previous blog in this series, “Why Lubricate?”

by Diana Pereda

Commenting to Ana Maria Delgado CRL with LUDECA, about the bearings and the lubricants that keep them operating, it occurs to me to write about a point of view that few people observe.

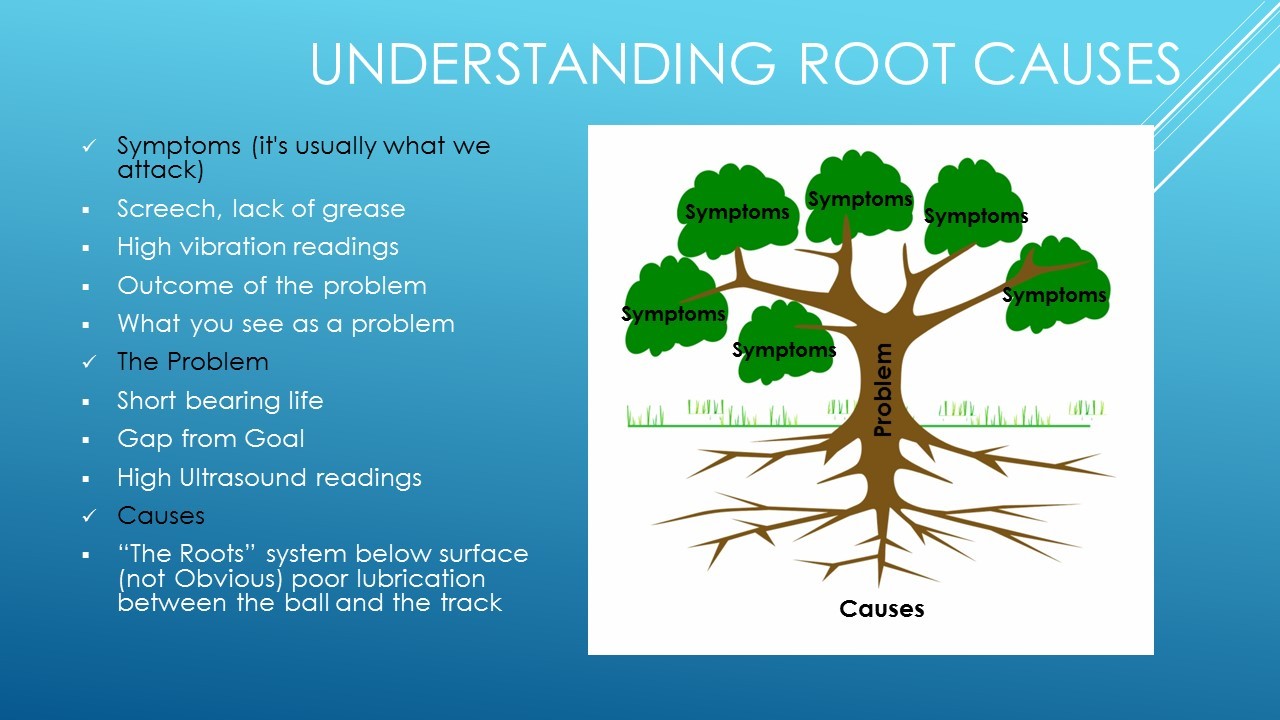

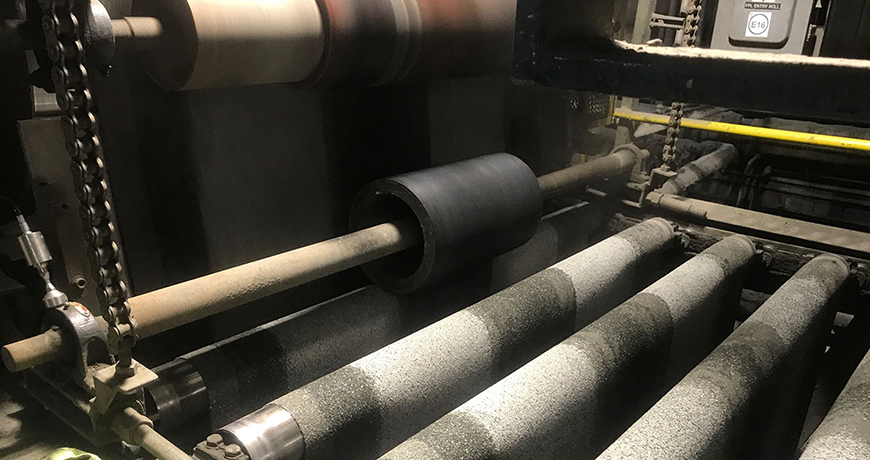

When we talk about lubricants, and regularly when referring to bearings, we talk about grease. Where the grease really performs its work, is at the point of contact of the ball or roller and the inner or outer race. The rest of the grease in the bearing housing does not perform lubricant work. The problems begin when we have to re-grease it, the regreasing of bearings is very particular, the type of grease, the correct amount, at the right time. This is something we hear in lubrication training, particularly on the way to World Class Lubrication. However, when you know the tools of Lean Six Sigma, you are always looking for the True Root Cause.

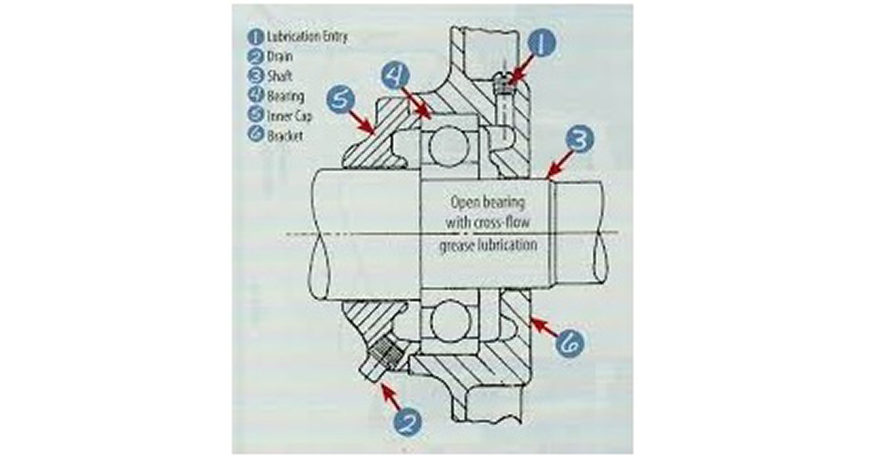

But at some point we have thought about the bearing housing, where the grease enters the housing, what is the route to the bearing, and more importantly where the grease residues damaged by time and temperature leave, not counting current discharges in the case of electric motors. In that passage, it is important that the grease that enters displaces the grease inside the cavity, that the grease that enters pushes the grease that is between the ball and the track, thereby relieving the bearing load. Not being less important that the grease that has finished its useful life goes outside, it does not lead to the winding in the case of electric motors.

If we stop to think about the cavities of the bearings, there are many readings about it, but a writing from Heinz P. Bloch P.E. comes to mind, for a Pump Symposium in 2015, “Lubrication Delivery Advances For Pumps and Motors Drivers”, One of the best writings on the topic of bearing lubrication, thanks to H. P. Bloch, I recommend you read it. This paper puts you to think about the importance of the passage of grease through the bearing and how it has to be allowed to evacuate the grease that has ended its useful life inside the bearing housing.

Of all types of bearing housing, only the one that allows cross-flow of grease when lubricating is ideal. When add grease to a bearing the grease under hydraulic pressure of the gun will move through all possible cavities, but if we give a relief on the opposite face of the bearing where the grease entry is, then it will do its job, to remove the spent grease and accommodate the new grease between the ball and the inner and outer race, extending the useful life of the bearing, avoiding maintenance interventions, improving productivity.

Reading the letter of Mr. Heinz P. Bloch, reminds of an old friend his beginnings in the industry, when he just graduated from college, he was in probation and have to go through the different facets of Manufacturing, and then Maintenance, he had to work directly with an industrial mechanic, who did not like to teach, therefore he had to learn by looking, without asking questions, he forced it, “which he thank him ”, to look at all the details in the mechanical assets, how many threads the screws have, the size of the pipe, if the bearings were balls or rollers, where the grease enters the bearings in the electrical motors, the right tool for the job, etc.

He forced him to speak the language of the bearings, to touch them carefully and capture the operating temperature, to make contact with the nail and appreciate the vibration, to listen and smell the condition of a rotating asset, it is interesting.

The grease has to come into contact with the ball and the track, if the Bearing Housing does not allow the new grease to displace the old grease and come into contact with the ball and the track, the bearing will fail, it will be long term but the fatality will occur, or you will have unwanted mechanical interventions of rotating assets. The training of technicians who perform the lubrication task is very important, for them to understand this.

by Diana Pereda

It seems a simple question, yet when asked, the answers are not always similar, or simple.

Some say, “to fight friction” and that is true. We do add grease to an asset’s moving parts to reduce friction. But there’s more to it than that.

Some say, “to reduce heat” and that is also true. The right amount of lubricant does help keep moving parts from getting too hot. But some lube techs, thinking more is better, take it to the extreme. They add more grease — thinking they are doing good — and instead choke the machine’s ability to disperse heat.

The real reason to lubricate assets is to form separation between surfaces. This logic applies to not only motor bearings. The pistons in an engine, chains on a chain drive, gears in a reducer, even linear bearings that do not rotate, but slide back and forth. The primary purpose to lubricate physical assets is to keep moving surfaces from coming into contact with each other. Because when they do, failure modes are initiated, and lifecycle is shortened.

Friction is a force which opposes movement between surfaces. Friction increases wear between surfaces, increases system temperature, and dramatically increases power consumption. The right amount, and type of lubricant creates a thin film between two surfaces. For as long as that film is maintained, it protects the asset from wear and heat while allowing it to produce in an energy efficient way.

Some lubricants offer the additional benefit of controlling corrosion. They contain additives which prevent rust from acid and water attacks.

Grease must be kept free of contaminants, but the very nature of the thickener allows it to pick up dust and grit. Proper storage is therefore crucial, and clean grease applied properly can actually shield machines from the ingress of contaminants.

We welcome you to read the previous blog in this series, “Three Myths About Greasing Bearings.”

Download our Oil & Grease Storage Best Practices for more tips to help outline the best practices for proper lubrication storage.

by Diana Pereda

I attended a training recently on the Easy-Laser XT770 alignment system at an oil and gas fracking company in West Texas. During the training I heard the term “grease worms” and even though I have been in the lubrication field for 29 years, I was unfamiliar with this animal.

Come to find out, it is a term used to describe an application completely devoid of any grease. In other words, someone didn’t grease the equipment at all and according to the guilty parties, these fictitious “grease worms” must have eaten the grease!

That got me thinking about the different oil viscosities and grease thickeners and how not all greases are created equal. We must look at each application individually and determine the correct oil viscosity and the correct thickener or “soap” that will work best in the application. You see, the thickeners have different characteristics that affect the performance. The term “LETS” can get us close to our final selection.

In conclusion, LETS investigate each application on its own merits to make the best final determination for which grease should be used; and, precision lubrication using ultrasound can help ensure that the right amount of grease is being used, and might just help avoid the infiltration of the dreaded “grease worm”!

by Diana Pereda

Once you understand how grease actually works to lubricate a bearing, it becomes obvious why over-greasing causes so much trauma to both bearings and the grease itself. Remember, all we want from our lubricant is to provide a little separation in the war zone. Nothing more… nothing less.

If you’re reading the term “war zone” for the first time, we use that term to describe the region of the bearing where all the wear and tear occurs.

Now let’s dispel three myths about greasing bearings.

Enough bad practices, please. We need a greasing strategy, but more than this, we need a greasing culture. Bad greasing culture will eat good greasing strategy for lunch. It only takes one bad actor, often well-intentioned – to destroy an asset.

Thank you Allan Rienstra with SDT Ultrasound Solutions for sharing this informative article!

Check out our LUBExpert, the ultrasound solution to avoid grease-related bearing failure! Plus, download our 5-Step Acoustic Lubrication Procedure an effective lubrication procedure to grease bearings right.

by Diana Pereda

Simply stated, viscosity is defined as the internal resistance of a fluid to flow. That doesn’t sound too difficult, does it? Unfortunately, new temperature, speed and pressure demands on lubricating fluids have changed over the years, resulting in several different measurements and classifications being created to describe lubricant viscosity.

Some examples are SUS, cSt, cP, ISO, SAE engine, SAE gear and AGMA; it’s enough to make a person’s head spin.

As mentioned above, viscosity is a physical measurement of a fluid’s internal resistance to flow. Assume that a lubricating fluid is compressed between two flat plates, creating a film between the plates. Force is required to make the plates move, or overcome the fluid’s film friction. This force is known as dynamic viscosity. Dynamic viscosity is a measurement of a lubricant’s internal friction and is usually reported in units called poise (P) or centipoise (1 P = 100 cP). A common tool used to measure dynamic viscosity is the Brookfield viscometer, which employs a rotating spindle that experiences torque as it rotates against fluid friction.

A more familiar viscosity term is kinematic viscosity, which takes into account the fluid density as a quotient of the fluid’s dynamic viscosity and is usually reported in stokes (St) or centistokes (1 St = 100 cSt). The kinematic viscosity is determined by using a capillary viscometer in which a fixed volume of fluid is passed through a small orifice at a controlled temperature under the influence of gravity.

Grease viscosity, traditionally called consistency, cannot be measured using the tests noted above. However, it is still relevant for selection of the correct grease for a specific application. Greases are fluid lubricants enhanced with a thickener to make them semi- solid. They usually are used in applications where a liquid lubricant would run out. Greases are sold by consistency grade, which in this case will be used synonymously with viscosity grade.

Grease consistency is measured using the cone penetration test. The National Lubricating Grease Institute (NLGI) created grade ranges for greases that have become the industry standard. These ranges characterize the flow properties of greases.

Various conditions must be considered when specifying the proper viscosity of a lubricant for a given application. These conditions include the operating temperature, the speed at which the specific part is moving, and the load placed upon the part. One other consideration is whether or not the lubricant can be contained so that it remains present to lubricate the intended moving parts.

The viscosity of a lubricant changes with temperature – in almost all cases, as the temperature increases, the viscosity decreases; and – conversely – as the temperature decreases, the viscosity increases. To select the proper lubricant for a given application, the viscosity of the fluid must be high enough that it provides an adequate lubricating film, but not so high that friction within the lubrication film is excessive. Therefore, when a piece of equipment must be started or operated at either temperature extreme – hot or cold – the proper viscosity must be considered.

The speed at which a piece of equipment operates must also be considered when specifying the proper lubricant viscosity. In high-speed equipment, a high-viscosity lubricant will not flow well in the contact zones and will channel out by fast-moving elements of the equipment. On the other hand, low-viscosity lubricant would have too low a viscosity to properly lubricate slow-moving equipment, because it would run right out of the contact zone.

Equipment loads must also be considered when selecting the proper lubricant viscosity. Under a heavy load, the lubricant film is squeezed or compressed. Therefore, a higher viscosity lubricant is needed. The higher the viscosity, the more film strength the lubricant will generally possess. In addition, the load can be either a continuous or shock load. A continuous load is a steady load that is maintained while the equipment is operational, while a shock load is a pounding or non-steady load. Under shock-load conditions, a low- viscosity lubricant would not possess enough film strength to stay in place, whereas a high-viscosity lubricant could stay in place and act like a cushion in the contact area.

In some applications in which a fluid lubricant would leak out, a grease might be recommended. However, it is still important to consider both the base fluid viscosity and the NLGI grade when selecting the proper lubricant. If the lubricant’s viscosity or consistency is too high, it might not flow where it is needed and the lack of lubricant – a condition known as lubricant starvation – would lead to metal-to-metal contact. This would cause wear that could ultimately result in equipment failure. The same thing could happen with a lubricant with too low a viscosity or consistency, because it might not stay in the area where it is needed.

With the SDT LUBExpert you have the ability to check on-condition lubrication and machine health using ultrasound.

Simply stated, viscosity is defined as the internal resistance of a fluid to flow, but it is probably the most important property of a lubricant. It can affect how the lubricant will function in a piece of equipment. If the wrong lubricant viscosity is selected for an application, the chances for equipment failure are dramatically increased.

Fortunately, organizations like ASTM, SAE, AGMA, ISO and others have created standards for lubricant viscosity and consistency that are to be used as guidelines when selecting the proper lubricant.

The best rule is to always check the original equipment manufacturer’s manual for lubricant viscosity recommendations. If the OEM makes no recommendations, the next step is to consider the operating speed, temperature and load of the application to be lubricated. Another suggestion is to contact lubricant manufacturers for recommendations; they often can provide technical support for proper fluid or grease selection.

After making a lubricating product selection, it is important to closely monitor the equipment to ensure the right choice was made. If possible, visually observe the moving parts to verify that a sufficient lubricant film is present to protect them. If not, listen for any unusual load grinding, chattering or squalling noises, which often are indications of metal-to-metal contact.

Thank you John Sander with Lubrication Engineers for this educational and informative article!

by Diana Pereda

Dirt particles as small as 5 microns can easily damage bearings and gears in equipment. Unfortunately, gearbox vents and hydraulic breather caps only prevent particles larger than 25-45 microns from being ingested into machinery from the surrounding air. As a result, those large particles are broken down into much smaller particles resulting in premature equipment damage. For example, one teaspoon of dirt in a 55 gallon drum of lubricant can create one billion particles that are 4 microns or larger in diameter in that same drum. Imagine how much damage this can cause in equipment, leading to unwanted maintenance downtime.

Additionally, these vents and caps provide no protection from moisture ingress into equipment. Water is one of primary defect sources for industrial machinery.

A good quality desiccant breather has a 3 micron filter as part of the design to help prevent harmful particles from being introduced into equipment. As a result, premature equipment failures, loss of capacity and unneeded maintenance expenses will largely be prevented.

Additionally, desiccant breathers provide an insight into the equipment health through how the desiccant is being spent.

It is very important to have good quality desiccant breathers installed on equipment to prevent the introduction of equipment defects and help improve your return on assets.

Note: The actual color changes above will vary depending on the supplier of the desiccant breather. All breathers will have some type of color change indicating condition. The above colors are applicable to two well-known desiccant breather manufacturers.

Learn more about Lubrication Best Practices and desiccant breathers from Paul Llewellyn at our Rethink Maintenance Training Roadshows

by Diana Pereda

Ultrasound is a guide to precision grease replenishment in motor bearings. It is also known for its versatility for leak detection, valve assessment and electrical fault detection.

Acoustic lubrication is an integral component of ultrasound programs. Fewer than 95 percent of all roller bearings reach their full engineered life span, and lubrication is the culprit in most cases. In fact, poor lubrication practices account for as much as 40 percent of all premature bearing failures. Yet, when ultrasound is used to assess lubrication needs and schedule grease replenishment intervals, that number drops below 10 percent. What would 30 percent fewer bearing related failures mean for an organization? Download our 5-STEP Acoustic Lubrication Procedure – An effective lubrication procedure to grease bearings right

To understand the role precision lubrication plays in bearing life extension, it helps to understand basics of bearings, their lubrication mechanism and how ultrasound helps.

The insides of a bearing consist of four components. The inner and outer raceways form a path for the rolling elements to glide on a thin film of lubricant. A metal cage separates the rolling elements, keeping them evenly spaced to distribute the load and stop them from crashing into one another. These components move in concert producing frictional forces from rotational inertia, surface load, misalignment, imbalance and defects. Zero friction is impossible, but optimal levels of friction are achievable with correct installation techniques and proper amounts of lubricant. Download our Induction Heating Procedure – Bearing Mounting – A simple and safe procedure for proper bearing installation

Ultrasound works on the FIT principle—it responds well to defects that produce friction, impacting and turbulence (FIT). For motor bearings, two of these phenomena apply: friction and impacting. Ultrasound detects high-frequency signals produced when two surfaces slide together or come in contact with any force. Stage 1 bearing failures happen at the micro level. Because ultrasound ignores low-frequency audible signals, it forms the perfect companion for measuring, trending and analyzing defects despite high levels of noisy interference encountered on the factory floor.

Ultrasound detectors detect friction and impacting as acoustic energy from rolling friction and defect impulses. When lubricant levels are optimum, the energy created is at its lowest. As frictional forces increase, so does the acoustic energy. Ultrasound instruments measure friction and impacting as energy using the scaled value dBµV (decibels/microvolt). The results are presented as condition indicators, and there are four of them:

Condition indicators are most responsible for transforming ultrasound technology from a simplistic, “point the gun and pull the trigger” gadget, to being recognized as analysis and trending technology. Condition indicators add validity to trending by going beyond the single decibel. If a user currently uses an ultrasonic gun that does not have condition indicators, they should question the data. Click here to read the entire article “Use Ultrasound to Optimize Grease Replenishment”

by Diana Pereda

Understanding the Key Components of an Effective Lubrication Program

Lubrication is often overlooked in organizations. Why it is overlooked, I am unsure. Maybe it is because it is considered to be a basic job, given to the apprentice, or it is just too simple not to do it correctly.

However, with a focus on lubrication, many failure mechanisms can be reduced and the equipment life prolonged. But implementing an effective and world-class lubrication program is not simple. It requires a dedicated focus to implement and sustain. Below is my list of what I look for when evaluating a lubrication program.

Effective lubrication takes many of the practices mentioned above and provides a governance framework to support and ensure it is executed as designed. With an effective lubrication program, the organization should see an increase in uptime, a reduction in lubrication consumption, and a reduction in the number of lubricants on site. These changes enable the organization to operate more efficiently.

Next Steps

To begin the journey to improve your lubrication program, you do not need a full assessment and massive project. Take one of the items above, learn more about it and start a pilot. Make sure to build a business case with your pilot to capture the benefits and use that as a basis to build the business case for the larger project.

Thank you James Kovacevic with Eruditio LLC for sharing this informative article with us!

by Diana Pereda

Maintaining proper oil levels in our equipment is a critical maintenance function to keep our assets running and producing product. Adding (or topping off) oil in our assets requires a means to transfer the lubricant from a container to the machine. The means used to accomplish this task are much more critical than may be commonly understood.

Does your facility use some type of funnel as a transfer mechanism? While funnels can make this task easier, they are not recommended because of their potential to introduce contaminants into the lubricant.

Funnels are usually stored in dirty environments in the plant and are therefore constantly exposed to dirt and dust. Even wiping off the funnel before use exposes the funnel to even more contaminants that enter into our equipment and cause damage.

As a lubricant flows through the funnel, it carries along all the dirt particles on the funnel straight into the machine. Not only large particles, but very small particles that can’t be seen with the human eye enter into the equipment and cause the most damage.

Another risk of funnels is the potential for cross-contamination between two incompatible lubricants. Many oils on the market, when mixed with another lubricant, can easily cause severe machine damage. Most funnels are not color-coded or labeled in a way that would designate them to be used only for a particular lubricant. Therefore, a number of different oils may flow through the same funnel, potentially contaminating the lubricant inside the machine and causing significant damage.

A sealable and reusable (S&R) container is a “best practice” alternative to a funnel. These containers typically have a spout or pump-style lid, making it easy to transfer lubricants from the lube room to a machine in the plant. However, the main benefit of these containers is that they lower the chance of particle ingression and cross-contamination into your equipment. This prevents equipment failures, unwanted downtime and improves plant capacity.

You can learn more about Lubrication Best Practices from Paul Llewellyn at our Rethink Maintenance Training Roadshows

by Diana Pereda

Best practice lubrication requires filtering out particles to the proper ISO code for the type of machine. One way to keep your equipment lubricant clean is by installing good quality desiccant breathers. Desiccant breathers replace the standard dust cap or OEM breather cap on equipment and provide much better particulate and moisture filtration. Not all desiccant breathers offer the same amount of protection. I recently visited a facility that was using desiccant breathers on their critical equipment. Unfortunately, these breathers only provided particulate filtration down to 10 microns, allowing harmful particulate ingression directly into their critical equipment and potentially creating unwanted equipment damage and downtime. This is why desiccant breathers with specific features will protect your critical equipment from damage and unnecessary repairs: A two-stage particulate filter system that incorporates a minimum of a 3 micron particulate filter and a “sponge” to capture oil mist that is contaminated is one such. A stand pipe within the breather that protects the reservoir from desiccant in the event of something breaking the breather while in application is also a good idea.

Check out Lubrication Engineers’ full line of desiccant breathers for contamination exclusion in industrial applications or learn more about Lubrication Best Practices from Paul Llewellyn at our Rethink Maintenance Training Roadshows

by Ana Maria Delgado, CRL

Guest post by Paul Llewellyn – LUBRICATION ENGINEERS

If manually greasing a bearing typically means that the bearing will end up being over-greased because more often than not the person doing the greasing pumps new grease in until new grease comes out the other side of the bearing, and over-greasing is as bad as under-greasing, then why don’t more facilities use fully automatic or single point lubricators which can prevent this problem? Let’s take a look at some of the positives associated with automatic lubrication and SPLs.

Advantages of a Single Point Lubricator (SPL):

If you are trying to improve the reliability program at your facility, consider automatic lubrication and Single Point Lubricators as a simple place to start. You will see immediate benefits with improved bearing life, parts and labor reductions, less unscheduled downtime and increased production and profits.

Learn more about Lubrication Best Practices from Paul Llewellyn at our Rethink Maintenance Training Roadshows

by Ana Maria Delgado, CRL

While we’ve been using calendars and calculators to determine grease replenishment requirements in bearings for a long time, this science is wrong. Most bearings never reach their L10 engineered life, and poor lubrication practices are attributed as the primary failure cause.

Bearings fail when they are over-greased. We lubricate them too often, and we use too much grease.

Change Your Thinking.

We lubricate bearings to manage friction, but over time, grease gets old and needs replenishment. The first sign is when friction levels increase. Ultrasound performs well at sensing and measuring changing in friction levels. It’s the perfect technology to guide lube technicians during the lubrication-replenishment task.

Lubrication Solution

We want to grease bearings correctly. That means using the right grease, at the right location, following the right procedures and intervals, injecting the right amount, and receiving the right feedback when the task is done. New technologies from SDT are engineered to do just that.

The days of relying on calendars and calculators are over. Use our 5-Step Acoustic Lubrication Procedure and start greasing bearings the right way!

Download our Ultrasound Lube Technician Handbook to learn more!

by Yolanda Lopez

Guest post by Paul Llewellyn – LUBRICATION ENGINEERS

Is new oil clean oil? That is a question that can be debated, and has been, for many, many years. If the new drum that was delivered to my dock, destined for my hydraulic equipment, has never been opened, how can the oil inside it be “dirty”?

To answer that question, perhaps we need to look at a typical journey for a drum of “new” oil. Most commercial oils leave the finished lubricant manufacturing location in a bulk tanker truck destined for several local oil jobber or distributor locations. First question: How clean was the tanker truck’s tank when the oil was pumped into it? What method was used to fill the tanker? Was a hose used that had been lying around the filling area floor? How many stops were made before the tanker arrived at your supplier’s location?

Once arrived at the jobber location, the oil is off-loaded into bulk storage silos on site. Again, what was the method used to off-load the bulk oil? Is there a dedicated pump and hose for each different type of oil being off-loaded and stored, or do they flush the same pump and hose and use just one? Where and how were the pump and hose stored?

Once on site, the oil then has to be transferred into the container that you ordered. Let’s say that’s a 55-gallon drum. Has that drum been used before and is simply refurbished for reuse? How was it cleaned? What oil was in it before? Is it rusty inside? Does it contain moisture? Dirt?

And what if you ordered a small tanker delivery of say 300 gallons for the 500-gallon stationary tank at your facility? Are you the first stop of the day for the delivery driver or has he been off road on dirt and gravel to five different construction sites before showing up at your facility? Was he/she trained in contamination control best practices? Most likely, they have no training in that area.

So, it is fairly easy to see how new oil can become dirty and most likely is too dirty for use in a hydraulic system. It is best practice to take an oil sample of the new oil upon arrival. This will tell you whether the oil in the container is actually the oil you ordered and what cleanliness level the oil meets. Then, best practices dictate that you filter that oil before you put it into your expensive equipment. And use dedicated pumping equipment for that fill. Don’t pay for the cost of reliability with the consequences of unreliability!

Learn more about Lubrication Best Practices from Paul Llewellyn at our Rethink Maintenance Training Roadshows

Download Oil & Grease Storage Best Practices

by Ana Maria Delgado, CRL

by Yolanda Lopez

Guest post by Paul Llewellyn – LUBRICATION ENGINEERS

As with so many things, such as dogs, all greases are not the same. There are greases that are made simply to meet the slimmest of specifications and then there are greases designed to far exceed basic performance specifications.

Greases are primarily made up of oil (70%-95% base oil) of a certain viscosity that is held (like water with a sponge) with some type of thickener, also called a soap. Next, there are additives to increase performance characteristics of the grease, such as extreme pressure additives, additives to protect protect the surface of the metal (such as rust and corrosion inhibitors), and additives to protect the grease itself, such as anti-oxidants.

Additionally, the soap, or thickener itself, will have certain desired performance features. If moisture is the primary concern, one should choose a grease where the thickener itself has good water wash out/spray off resistance capabilities (such as an aluminum complex or calcium sulfonate.) If heat is your main issue then perhaps a clay/bentone soap is the best choice. Additionally, industry has chosen a polyurea thickener for electric motor grease applications because of its stability and oxidation resistance. It is important to note that not all grease based oils or thickeners are compatible, and when mixed, can cause serious issues and ultimately lead to bearing failure.

Finally, we are our own worst enemy when it comes to handling the greases we put into the bearings. We introduce contamination with poor storage and handling practices (such as leaving the lid off the grease keg) or introducing a dirty grease pump into a new container. Be sure to take precautions when handling and applying grease to expensive bearings since unscheduled downtime is very costly. Remember, not all greases, bearing designs or operating conditions are the same: choose your grease wisely!

Download Oil & Grease Storage Best Practices

by Ana Maria Delgado, CRL

Are you adding grease to a bearing and not hearing any changes from your ultrasound equipment? If so, start wondering where the grease is going. It is a fact that if grease gets into a bearing the ultrasound decibel will either go down on a bearing that needs grease or go up on a bearing that is already over-lubricated.

Look for a blocked grease tube. Grease may be going into the windings on an electric motor. Do you see grease on the tube of the grease gun? Maybe a greaseable bearing was replaced with a sealed bearing at the motor shop after a repair. These are just some of the things you need to consider if you get no ultrasonic decibel change after injecting grease to a bearing.

Download 5-Step Acoustic Lubrication Procedure

by Yolanda Lopez

Thank you Juan R Márquez with Eli Lilly and Company for sharing this informative article on bearing lubrication with us!

Download our Oil & Grease Storage Best Practices which includes helpful tips to outline the best practices for proper lubrication storage.

Related Blog: How to Grease Your Bearings Using Ultrasound?